Adult Learners in SLW (Part 2): Using Graphic Organizers

by Joy Kreeft Peyton

In the first

article in this series, Rebeca Fernandez provides guidance on

designing a course that provides adult English learners with multiple

opportunities to use writing toward personal, academic, and professional goals.

(See also discussion of these in Fernandez et al., 2017). The list of what

learners need to be able to do in writing is long; mastering these skills is

not easy; and students often feel anxious, alone, and unsupported as they seek

to fulfill writing assignments which the teacher, often a native speaker of

English, will read and judge (Martinez et al., 2011; Minahan & Schultz,

2015). In order to support them, teachers need to

-

develop and implement

activities that connect oral language, reading, and writing that is related to

the content that is the focus of instruction;

-

develop topics and

structure for the writing;

-

align these with the

writing standards followed in the program; and

-

ensure, through ongoing

observation and assessment, that learners are developing these skills and

abilities.

Providing many opportunities for learners to engage in academic and

professional writing and providing clear, specific, visible supports for

developing this type of writing is critical. Ferlazzo (2017) and Lee (2017)

argue that the ability to produce written products at this level is achievable

when students have appropriate supports of teacher guidance and scaffold-rich

curricula.

Providing Scaffolds for Writing

There are a

number of perspectives on ways to help learners be successful writers through

supported interaction, scaffolding in the zone of proximal development, and

apprenticeship. Vygotsky (1962, 1968) described the process of learning in the

space or “zone of proximal development,” in which the learner is working to

solve a problem or accomplish a task, and the teacher or a more competent peer

“scaffolds” the learning by working collaboratively with the learner and

demonstrating ways to move forward.

One type of

scaffold and support that can help adult learners develop proficiency with academic

writing is graphic organizers, which provide a framework for shaping key ideas

in a written piece. Also known as a knowledge map, concept map, story map,

cognitive organizer, advance organizer, or concept diagram, a graphic organizer

uses visual symbols to represent knowledge, concepts, thoughts, or ideas in a

text and show the relationships among them.

Using Graphic Organizers in

Instruction

Jiang and

Grabe (2007) conducted research on the use of graphic organizers in reading

instruction and concluded that they are an effective way to facilitate text

comprehension because they make the structure of texts visible. Here, we focus

on the use of graphic organizers to develop ideas for and approaches to writing

an academic text with learners at different levels.

Wrigley and Isserlis (n.d.) provide examples

of graphic organizers that can be used in adult English as a second

language (ESL) literacy classes at many different levels of ability, fluency,

and comfort with reading and writing. They argue that graphic organizers

provide opportunities for basic-level literacy learners (in any language) to

contribute content and information and to raise topics and questions of interest

as part of the process of developing oral and written language (e.g., getting

to know one another, listing languages that they speak, listing favorite

activities). LINCS

and KET

Education also have helpful resources for using graphic organizers

with adult learners.

Two commonly

used graphic organizers are a KWL chart and a Venn diagram, which are widely

used in K–12 and adult education. Here, I give an example of how each one could

be used in an adult education class, with the focus and vocabulary of a specific

lesson topic. In the next sections, I describe less commonly used graphic

organizers.

Table 1 shows a KWL chart developed by a class that

is studying, thinking about, and using vocabulary related to climate

change.

Table 1. Example KWL

Chart – Climate Change

|

Know |

Want to Know |

Learned |

|

Earth’s

temperatures are getting warmer. |

What are all of

the causes of climate change? |

Climate change is

caused by both natural changes to the earth and oceans and by human

activity. |

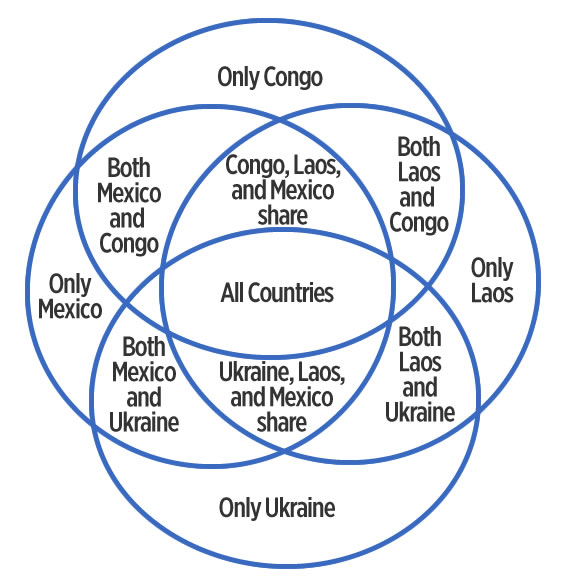

Another

topic that a class might focus on is key features of the countries of origin of

the students in the class. Students might work in pairs and complete a Venn

diagram, each focusing on their country. They would write the name of one

country at the top of one of the circles and the other country at the top of

the other circle. Working together, they would list features of their countries

that are different, in the outer part of the circles, and features that are the

same in the center section. This activity could lead to a considerable amount

of discussion, reading, and writing. If the entire class then came together to

consider the countries of origin of all of the students in the class, the Venn

diagram would have as many overlapping circles as the countries involved (see

Figure 1). The result could be writing informational pieces (about one’s own or

another person’s country), comparative writing (describing how the two countries

are similar or different), or argumentative writing (making a statement about

the key features of the two or more countries and defending it with data).

Figure 1. Example Venn diagram: countries students

are from.

Using Graphic Organizers With

Students at Different Levels

Graphic

organizers can be used with adult English learners at different levels, from

low beginning and beginning to advanced. (Some of these examples come from

interviews that Kirsten Schaetzel, Rebeca Fernandez, and I did with adult ESL

teachers about ways that they teach writing. The approaches are described in

more detail in Peyton & Schaetzel, 2016.)

Scaffold 1: Writing

Support

Beginning Literacy and Low

Beginning Proficiency Levels

One teacher

whom we interviewed works with adult learners who are beginning writers. She

scaffolds their writing as they move from writing a single sentence to a

paragraph. The writing support that she provides is a simple statement on the

board each day with the date, which the learners copy in their notebooks:

➣ Today is Monday, February

19, 2018.

After a few

weeks, she adds a second sentence, like one of these:

➣ Today is Presidents' Day.

➣ The weather today is

cold.

The students

copy both the date sentence and the new sentence. Later, without having written

on the board, she asks them to write two sentences in their notebooks; students

have their previous writing in their notebooks to use as models. It is easy to see

how this simple writing support could develop over time, until the students are

continually writing topic-focused paragraphs about the content on the board or

in their notebooks.

Scaffold 2:

Conversation Grid

Beginning Literacy and Low

Beginning Proficiency Levels

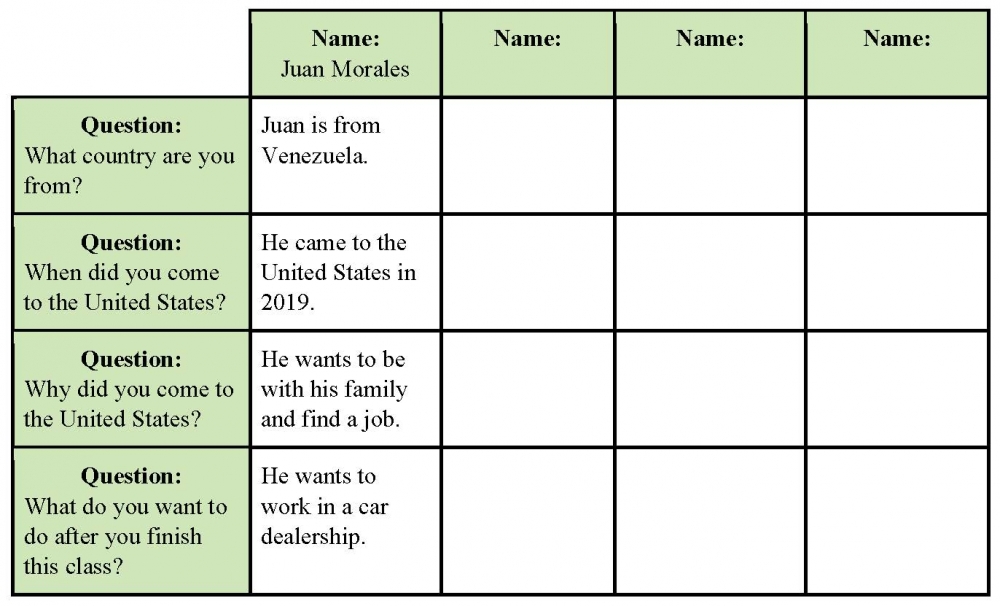

Another

writing support that a teacher we interviewed uses is a conversation grid. Each

student has a piece of paper with four student names across the top and four

questions in a column down the left side of the page. Each student goes to four

different students, asks one of the four questions of each

student, and writes the answer in the appropriate space in the grid. Table 2

gives example questions and the answers for one student.

Table 2. Conversation

Grid Example: Asking About Backgrounds and Interests

(Click here to enlarge.)

This simple

exercise can build over time, to more and more complex writing. Students might

start by writing a few words (e.g., Juan, 2019, family and job; cars) and

gradually move to writing phrases and then sentences, as this student did. They

might move to asking each student they talk with all four questions, writing

the answers in the spaces in the grid, and then writing summaries of the

responses, comparing the responses, and sharing with others (orally or in

writing) a summary of what they have learned. Like the previous examples, this

can lead to informative/descriptive writing, comparative writing, and

argumentative writing. That is, a teacher can start with a relatively simple

activity and build it over time.

Scaffold 3:

RAFT

Intermediate Levels and

Multilevel Classes

Students at

intermediate levels are often part of multilevel classes, which can present

challenges for teachers seeking to facilitate the writing of students with

different background knowledge and language proficiencies.

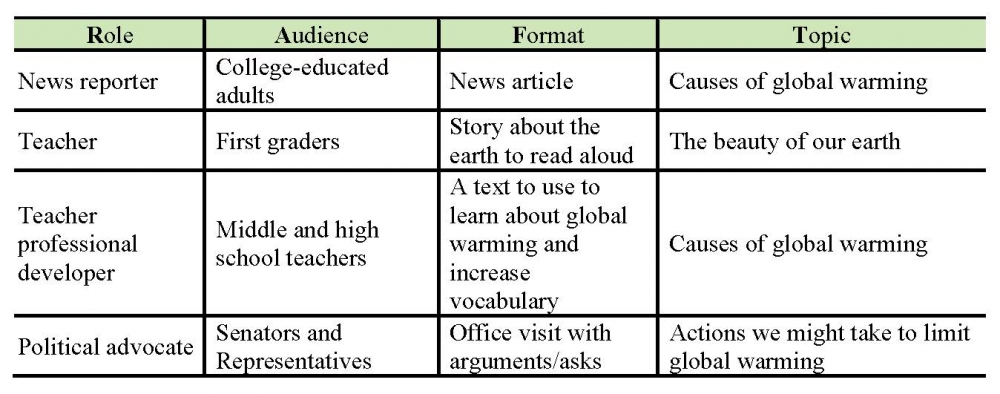

One graphic

organizer that students can use alone or in groups, at their proficiency level,

is RAFT, in which they think about a piece of writing from different

perspectives and fill in a chart, answering these questions, before they begin

to write a paper.

Role:

Who am I as a writer?

Audience:

To whom am I writing?

Format:

What form will the writing take?

Topic:

What is the subject or focus of the piece of writing?

Calderón et

al. (2018) give an example of what these components might look like in

different writing activities. See Table 3 for an example I’ve created in a

similar format. These components would be adjusted by the teacher and the

students, depending on students’ interests and proficiency levels and the focus

of the class, unit, or lesson.

Table 3. RAFT Example:

Global Warming

(Click here to enlarge.)

Completing the RAFT chart for different writing

pieces gives students opportunities to explore different genres, styles, and

tones and to consider different points of view on a topic. It also helps

students to frame what may seem like an overwhelming assignment, to begin

thinking about what they will write, and to lessen their anxiety in completing

the assignment.

Here is an

example of a blank chart that students might fill in. Students would complete

each section, alone or in pairs or small groups, and then develop their piece.

|

Role

|

Audience |

|

Format |

Topic

|

|

Writing

Piece

|

|

Scaffold 4: Force Field

Analysis

Advanced

Levels

Finally,

students at advanced levels need to be able to enter fully into the endeavor of

writing academic texts. While they bring a considerable amount of language

proficiency and personal resources to the task of writing, now they need to

complete more high-stakes writing assignments.

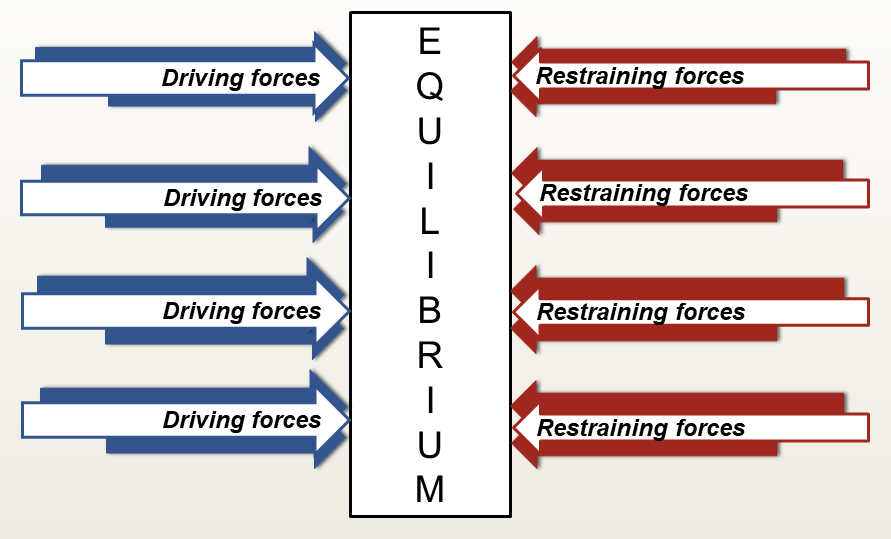

One graphic

organizer for doing this that has been adapted and used by an adult English as

a foreign language educator is Force

Field Analysis (Van Bogaert, 2017). It was created by social

psychologist Kurt Lewin in the 1940s as a guide for individuals to make a

decision or a change in their lives by analyzing the forces for and against a

particular topic or proposed change and considering or communicating the

reasons behind the decision. Using this graphic, individuals or groups in a

class can consider both “driving” forces (that would promote change) and

“restraining” forces (that would inhibit change). (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Force field analysis example.

In life

generally, this can be a helpful way for students to think through personal

decisions, life goals, and responsibilities. When used to support writing

development, it can be a way to “unstick thinking”:

-

visually represent

different views about or approaches to a topic,

-

organize those views in a

systematic way,

-

generate ideas and develop

a thesis or opening statement,

-

support the ideas

generated, and

-

explore perceptions or

opinions of opposing parties.

With her

university students, Van Bogaert (2017) used this graphic to generate and

organize points that were relevant to papers they were writing. For example,

working together, they generated ideas for a paper about why action on climate

change has been limited, articulating driving forces (some people are pushing

for industry changes) and restraining forces (some industries do not want to

change), which includes recognition of different perspectives on its reality

and its impact on different individuals and sectors of society.

Conclusion

We have been

able to see that students engaged in academic writing need not only continuous

practice with writing and effective feedback on the writing they produce, they

also need supports that place them in a community of

writers and help them to generate and organize their ideas before they begin writing and while they are developing ideas or expressing them in a piece of writing.

In the final article of this series (Part 3) on teaching adult learners second

language writing, Kirsten Schaetzel discusses the use of test prompts to guide

the teaching of academic writing.

References

Calderón, M.

E., Slakk, S., Carreón, A., & Peyton, J. K. (2018). ExC-ELL:

Expediting comprehension for English language learners (3rd ed.).

Margarita Calderón & Associates.

Ferlazzo, J.

(2017, April 22).Ways to teach ELLs to write academic essays: A discussion with

Larry Ferlazzo. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-response-teaching-ells-to-write-academic-essays/2017/04

Fernandez,

R., Peyton, J. K., & Schaetzel, K. (2017, Summer). A survey of writing

instruction in adult ESL programs: Are teaching practices meeting adult learner

needs? Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy,

Secondary, and Basic Education, 6(2), 5–20.

Jiang, X.,

& Grabe, W. (2007). Graphic organizers in reading instruction: Research

findings and issues. Reading in a Foreign Language, 19(1),

34–55.

Martinez, C.

T., Kock, N., & Cass, J. (2011). Pain and pleasure in short essay

writing: Factors predicting university students’ writing anxiety and writing

self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,

54(5) 351–360.

Minahan, J.,

& Schultz, J. J. (2015, January). Interventions can salve unseen

anxiety barriers. The Phi Delta Kappan, 96(4),

46–50.

Peyton, J.

K., & Schaetzel, K. (2016). Teaching writing to adult English language

learners: Lessons from the field. Journal of Literature and Art

Studies, 6(11), 1407–1423. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309467693_Teaching_Writing_

to_Adult_English_Language_Learners_Lessons_From_the_Field

Van Bogaert,

D. (2017, April 8). Force field analysis: A practical planning tool

for professional development. Presentation at the Conference on

Language, Learning, and Culture, Virginia International University, Fairfax,

Virginia, USA.

Vygotsky, L.

S. (1962). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L.

S. (1968). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological

processes. Harvard University Press.

Wrigley, H.,

& Isserlis, J. (n.d.). Into the box out of the box grids,

graphs, and ESL literacy. http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/sites/default/files/GridsSurveys.pdf

Joy

Kreeft Peyton is a senior fellow at the

Center for Applied Linguistics, in Washington, DC. Her work, which focuses on

language and culture in education, includes working with teachers and program

leaders in K–12 and adult education settings to improve their instructional

practice and study the implementation and outcomes of research-based practice.

Her work includes implementing and studying approaches to writing that

facilitate engagement and learning and promote academic and professional

success.