6 Self-Editing Strategies for L2 Writers

by Amy Cook

As writing teachers, we support our students through all

stages of the writing process. This article provides concrete strategies for

self-editing developed in my writing classes for English for speakers of other

languages (ESOL) undergraduate and graduate students at a public university. In

these classes, I make a distinction between revision, which addresses larger

scale changes (such as ideas and organization), and editing, which focuses on

grammar and mechanics. With these self-editing exercises, my goal is to

introduce students to strategies for finding and correcting mistakes in their

own writing.

Why We Should Teach Language Learners

Self-Editing Skills

There are several reasons I make time to focus on

self-editing with second language (L2) writers.

-

They ask for it: My

students often request structured guidance and support in self-editing—it’s a

skill they’d like to improve.

-

They need it: It’s

also a skill I believe my students need, particularly outside of ESOL classes,

where they are not likely to have the same level of support that I can provide

with sentence-level issues.

-

It gives them

confidence: Practicing the strategies in my classroom can give

students confidence to continue using the strategies in the future.

Thus, I’ve developed a series of self-editing

strategy guides for my L2 writing classes. My ultimate goal is to empower these

L2 writers by improving their independent writing and editing skills through practice

and reflection. The process pushes students to try some new strategies, knowing

some will work better than others for different individuals. In the end,

students should leave my class with a handful of strategies they can continue

to use.

It’s important, though, to acknowledge that

self-editing doesn’t necessarily lead to error-free writing, and that the

overall class focus is still on effective communication, while taking steps

toward greater accuracy (Ferris 2008).

The Method

I introduce self-editing by providing an overview

to students (Appendix A), outlining my aforementioned rationale. Then, I

present one self-editing strategy with each writing assignment throughout the

semester. For each strategy, I explain how and why it works, then students

practice with step-by-step instructions to guide them in applying the strategy

to their own writing.

Finally, students reflect on the strategy,

considering what kinds of changes they made and whether they would use the

strategy again in the future. Originally, I provided paper-based guides for my

students, but, more recently, I have adapted the format by creating graded

surveys in our LMS, Canvas. The most important consideration is that students

have clear, concrete instructions to follow as they work with their own

writing.

The Strategies

Here are short descriptions of the strategies I

most commonly present to students. In a given semester, I typically choose one

strategy for each writing project, depending on the course, student level,

specific assignments, etc. You can find the full guide with steps for students

in Appendix B. Please feel free to use or adapt with attribution.

1. Read

Aloud

For this simple strategy, students are asked to

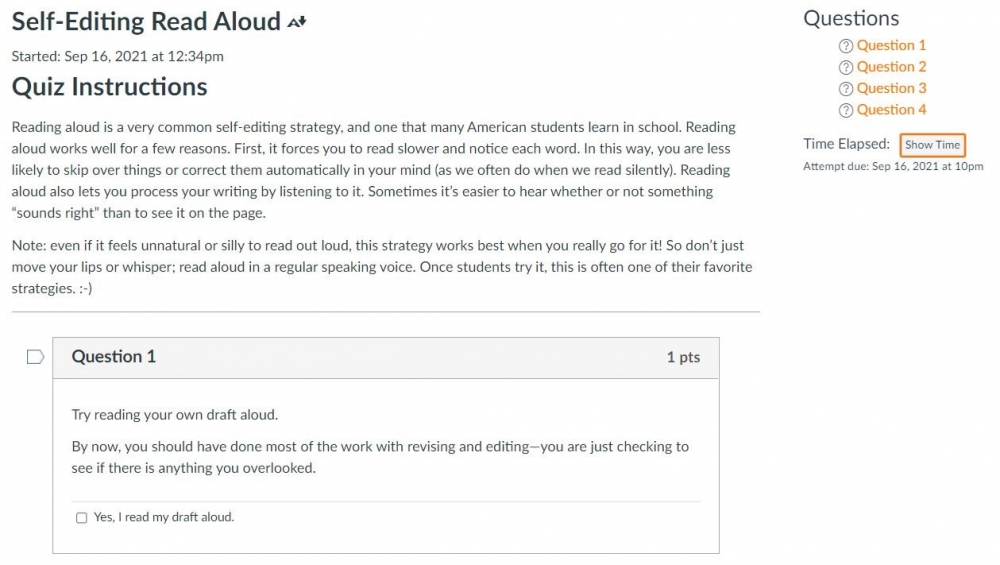

read their draft out loud (see the Figure; instructions partially adapted from

Ferris, 2014). This helps to slow them down and hear mistakes they may not

notice when reading silently. Although this strategy is widely known among

writing teachers, I have students each semester who have never tried it before!

Tip: students who struggle with oral

fluency may benefit from using a text-to-speech program and listening rather

than reading aloud themselves.

Figure. Screenshot of Canvas graded survey for read

aloud strategy. (Click here to enlarge)

2. Reading

Strategies

After asking students to read aloud, I present

three additional reading strategies that help students slow down and/or see the

writing with a new perspective:

Printed Copy

Students print a paper copy of the draft to see

what they notice on a printed page that they didn’t see on the screen. (How

many times have we, as teachers, noticed a mistake in our own course materials

only after printing the copies for the whole

class?)

Reading Backward

Students start with the last sentence of the draft,

and read it backward, sentence-by-sentence. This removes the writer from the

flow of ideas, so that sentence-level issues are easier to notice.

Reading Line-by-Line

Here, students can read on screen, by adjusting the

size of the word processor window, or on paper, by covering up a printed copy

with another piece of paper and revealing one line at a time.

3. Pattern of

Error

Here, students choose one area to focus on, looking

only for those types of mistakes (partially adapted from Ferris, 2014).

Sometimes students are already aware of grammar areas they typically struggle

with. These are some common areas I also recommend for students who aren’t sure

what to focus on:

- Verb form and/or verb tense

- Subject-verb agreement

- Noun endings (plural, possessive)

- Articles

- Punctuation and/or run-ons and/or

fragments

This kind of editing takes a lot of time, but it’s

very effective. It helps students notice more mistakes because they are

focusing their attention to look for them. It also helps students review the

rules for common trouble areas, and making repeated corrections should help

writers make fewer mistakes in the future.

If there are several areas writers want to check, I

suggest editing in multiple rounds—each time focusing on just one area.

4. Time

This is another simple strategy, but it requires a

bit of planning ahead. Students take a break of at least 30 minutes (or even

better, overnight), then proofread their draft. Taking a break and seeing the

document with “fresh eyes” helps students to notice things they wouldn’t have

otherwise.

5. Tech

Tools

There are many tools that can help writers improve,

but no tool is perfect! I suggest that students try out several tools, and take

note of what each tool can and can’t help with (instructions partially adapted

from Ferris, 2014). Most students already use the word processor spell and

grammar checkers, for example. Here are some other technology tools I recommend

to students:

Ludwig

(also an app)

This free site lets students type in a sentence or

phrase and see other examples of similar phrases. Students can compare their

writing to authentic samples to see if they might need to make corrections. See

instructions here.

Virtual

Writing Tutor

This is a free spell/grammar checker designed for

L2 writers. It has other features, too, like help with paraphrases and

vocabulary. There are explanations about all these features on the site, some

with explainer videos.

Speech recognition and

text-to-speech

- Speech recognition allows a device to type words

users say out loud. Some students find it easier to process ideas by talking

first, so they can use speech recognition to create a first draft by talking

instead of typing.

- Text-to-speech allows devices to read out loud to

users. This can help students use their listening skills to help with reading

as well as editing.

- Specific tools:

- Microsoft Office and Windows (instructions here

and here)

- Google Docs Voice Typing (instructions here)

- Apple Dictation for i0S (instructions here)

- Natural

Reader (free & paid versions)

With all of these tools, it’s important to remind

students to rely on their own knowledge and experience to help them make the

best decisions about their own writing. Each tool can be useful, but they are

not perfect. Ultimately, writers have to be responsible for their own work by

evaluating the advice from tech tools carefully. I also remind students that

there are no shortcuts to becoming a better writer—they must practice writing!

6. Your

Choice!

After trying several of the above, students pick

which one(s) to use. I often provide this option toward the end of the

semester, either on a final project or a reflective piece. It is always

interesting to see what students choose and why.

The

Takeaways

I imagine this list of self-editing strategies

includes some that you’re already familiar with, and I hope it also includes

some fresh ideas you’d like to try with your students. In my experience,

students appreciate the chance to try a variety of strategies, and they usually

encounter a few that they continue to use on their own. In a recent class,

nearly half of the students specifically mentioned self-editing in their final

projects, showing that it was a useful and memorable class activity.

Note: This article is based on the

presentation “Self-Editing Strategies for L2 Writers,” delivered at the TESOL

International Convention, March 2022, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

Ferris, D. R. (2008). Students must learn to

correct all their writing errors. In J. M. Reid (Ed.), Writing myths:

applying second language research to classroom teaching (pp.

90–114). University of Michigan Press.

Ferris, D. R. (2014). A guide to college

writing for multilingual/ESL students. Fountainhead Press.

Suggested

Resource

Ferris, D. R. (2011). Treatment of error in second language student writing (2nd

ed.). University of Michigan Press.

Amy

Cook is originally from Albuquerque, New

Mexico, where she completed a BA in languages and Latin American studies. She

also holds an MA in teaching English as a second language from the University

of Arizona. Amy is a teaching professor in the Department of English at Bowling

Green State University in northwest Ohio, USA. She enjoys working with a wide

variety of students in the ESOL, TESOL, and University Writing

Programs.