As writing teachers, we support our students through all stages of the writing process. This article provides concrete strategies for self-editing developed in my writing classes for English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) undergraduate and graduate students at a public university. In these classes, I make a distinction between revision, which addresses larger scale changes (such as ideas and organization), and editing, which focuses on grammar and mechanics. With these self-editing exercises, my goal is to introduce students to strategies for finding and correcting mistakes in their own writing.

Why We Should Teach Language Learners Self-Editing Skills

There are several reasons I make time to focus on self-editing with second language (L2) writers.

-

They ask for it: My students often request structured guidance and support in self-editing—it’s a skill they’d like to improve.

-

They need it: It’s also a skill I believe my students need, particularly outside of ESOL classes, where they are not likely to have the same level of support that I can provide with sentence-level issues.

-

It gives them confidence: Practicing the strategies in my classroom can give students confidence to continue using the strategies in the future.

Thus, I’ve developed a series of self-editing strategy guides for my L2 writing classes. My ultimate goal is to empower these L2 writers by improving their independent writing and editing skills through practice and reflection. The process pushes students to try some new strategies, knowing some will work better than others for different individuals. In the end, students should leave my class with a handful of strategies they can continue to use.

It’s important, though, to acknowledge that self-editing doesn’t necessarily lead to error-free writing, and that the overall class focus is still on effective communication, while taking steps toward greater accuracy (Ferris 2008).

The Method

I introduce self-editing by providing an overview to students (Appendix A), outlining my aforementioned rationale. Then, I present one self-editing strategy with each writing assignment throughout the semester. For each strategy, I explain how and why it works, then students practice with step-by-step instructions to guide them in applying the strategy to their own writing.

Finally, students reflect on the strategy, considering what kinds of changes they made and whether they would use the strategy again in the future. Originally, I provided paper-based guides for my students, but, more recently, I have adapted the format by creating graded surveys in our LMS, Canvas. The most important consideration is that students have clear, concrete instructions to follow as they work with their own writing.

The Strategies

Here are short descriptions of the strategies I most commonly present to students. In a given semester, I typically choose one strategy for each writing project, depending on the course, student level, specific assignments, etc. You can find the full guide with steps for students in Appendix B. Please feel free to use or adapt with attribution.

1. Read Aloud

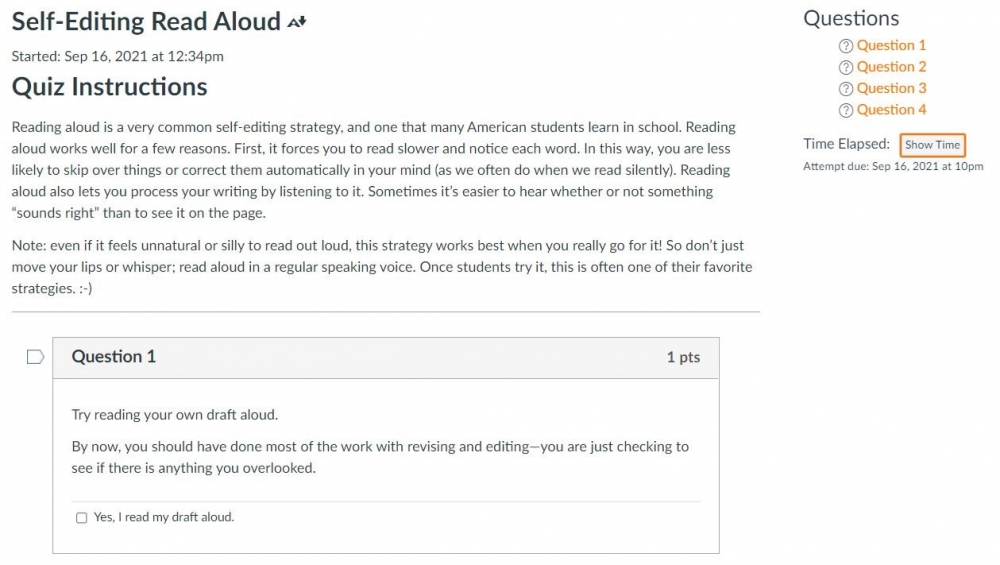

For this simple strategy, students are asked to read their draft out loud (see the Figure; instructions partially adapted from Ferris, 2014). This helps to slow them down and hear mistakes they may not notice when reading silently. Although this strategy is widely known among writing teachers, I have students each semester who have never tried it before!

Tip: students who struggle with oral fluency may benefit from using a text-to-speech program and listening rather than reading aloud themselves.

Figure. Screenshot of Canvas graded survey for read

aloud strategy. (Click here to enlarge)

2. Reading Strategies

After asking students to read aloud, I present three additional reading strategies that help students slow down and/or see the writing with a new perspective:

Printed Copy

Students print a paper copy of the draft to see what they notice on a printed page that they didn’t see on the screen. (How many times have we, as teachers, noticed a mistake in our own course materials only after printing the copies for the whole class?)Reading Backward

Students start with the last sentence of the draft, and read it backward, sentence-by-sentence. This removes the writer from the flow of ideas, so that sentence-level issues are easier to notice.Reading Line-by-Line

Here, students can read on screen, by adjusting the size of the word processor window, or on paper, by covering up a printed copy with another piece of paper and revealing one line at a time.

3. Pattern of Error

Here, students choose one area to focus on, looking only for those types of mistakes (partially adapted from Ferris, 2014). Sometimes students are already aware of grammar areas they typically struggle with. These are some common areas I also recommend for students who aren’t sure what to focus on:

- Verb form and/or verb tense

- Subject-verb agreement

- Noun endings (plural, possessive)

- Articles

- Punctuation and/or run-ons and/or fragments

This kind of editing takes a lot of time, but it’s very effective. It helps students notice more mistakes because they are focusing their attention to look for them. It also helps students review the rules for common trouble areas, and making repeated corrections should help writers make fewer mistakes in the future.

If there are several areas writers want to check, I suggest editing in multiple rounds—each time focusing on just one area.

4. Time

This is another simple strategy, but it requires a bit of planning ahead. Students take a break of at least 30 minutes (or even better, overnight), then proofread their draft. Taking a break and seeing the document with “fresh eyes” helps students to notice things they wouldn’t have otherwise.

5. Tech Tools

There are many tools that can help writers improve, but no tool is perfect! I suggest that students try out several tools, and take note of what each tool can and can’t help with (instructions partially adapted from Ferris, 2014). Most students already use the word processor spell and grammar checkers, for example. Here are some other technology tools I recommend to students:

Ludwig (also an app)

This free site lets students type in a sentence or phrase and see other examples of similar phrases. Students can compare their writing to authentic samples to see if they might need to make corrections. See instructions here.Virtual Writing Tutor

This is a free spell/grammar checker designed for L2 writers. It has other features, too, like help with paraphrases and vocabulary. There are explanations about all these features on the site, some with explainer videos.

Speech recognition and text-to-speech

- Speech recognition allows a device to type words users say out loud. Some students find it easier to process ideas by talking first, so they can use speech recognition to create a first draft by talking instead of typing.

- Text-to-speech allows devices to read out loud to users. This can help students use their listening skills to help with reading as well as editing.

- Specific tools:

- Microsoft Office and Windows (instructions here and here)

- Google Docs Voice Typing (instructions here)

- Apple Dictation for i0S (instructions here)

- Natural Reader (free & paid versions)

With all of these tools, it’s important to remind students to rely on their own knowledge and experience to help them make the best decisions about their own writing. Each tool can be useful, but they are not perfect. Ultimately, writers have to be responsible for their own work by evaluating the advice from tech tools carefully. I also remind students that there are no shortcuts to becoming a better writer—they must practice writing!

6. Your Choice!

After trying several of the above, students pick which one(s) to use. I often provide this option toward the end of the semester, either on a final project or a reflective piece. It is always interesting to see what students choose and why.

The Takeaways

I imagine this list of self-editing strategies includes some that you’re already familiar with, and I hope it also includes some fresh ideas you’d like to try with your students. In my experience, students appreciate the chance to try a variety of strategies, and they usually encounter a few that they continue to use on their own. In a recent class, nearly half of the students specifically mentioned self-editing in their final projects, showing that it was a useful and memorable class activity.

Note: This article is based on the presentation “Self-Editing Strategies for L2 Writers,” delivered at the TESOL International Convention, March 2022, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

Ferris, D. R. (2008). Students must learn to correct all their writing errors. In J. M. Reid (Ed.), Writing myths: applying second language research to classroom teaching (pp. 90–114). University of Michigan Press.

Ferris, D. R. (2014). A guide to college writing for multilingual/ESL students. Fountainhead Press.

Suggested Resource

Ferris, D. R. (2011). Treatment of error in second language student writing (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Amy

Cook is originally from Albuquerque, New

Mexico, where she completed a BA in languages and Latin American studies. She

also holds an MA in teaching English as a second language from the University

of Arizona. Amy is a teaching professor in the Department of English at Bowling

Green State University in northwest Ohio, USA. She enjoys working with a wide

variety of students in the ESOL, TESOL, and University Writing

Programs.

| Next Article |