English language learners and teachers alike recognize articles as a particularly troublesome area of English grammar. Not only do numerous rules-of-thumb exist for the definite, indefinite, and zero articles (e.g., Cole, 2000), but learners inevitably find exceptions to those rules. In this article, I focus on the definite article and, using Cuisenaire rods, attempt to demonstrate how we, as teachers, can direct our students to see a consistent meaning across multiple uses of the.

English language learners and teachers alike recognize articles as a particularly troublesome area of English grammar. Not only do numerous rules-of-thumb exist for the definite, indefinite, and zero articles (e.g., Cole, 2000), but learners inevitably find exceptions to those rules. In this article, I focus on the definite article and, using Cuisenaire rods, attempt to demonstrate how we, as teachers, can direct our students to see a consistent meaning across multiple uses of the.

Traditional Rules

Three common article rules for the definite article are the following:

-

Use the with nouns that are unique.

-

Use the for nouns that have been previously mentioned.

-

Use the with the superlative.

Each of these rules fails to explain the meaning of the definite article. Why should learners use the with superlative forms or for the second mention of a noun? Why should learners use the before nouns that refer to unique things? And what does a term like unique (or specific and definite) actually mean? Finally, what do these rules have to do with one another?

Visualizing a Common Meaning

Perhaps, if we guide our students to visualize a common meaning for the definite article across its various uses, we will begin to unlock some of the mystery of this little, yet frequent, word for our students and for ourselves. You might be skeptical that there is, in fact, any consistent meaning to be found. After all, what commonalities can be found for use of the in the following examples?

-

Please choose the best answer.

-

They went to see a movie and were quite surprised by the ending.

-

Be sure to tell the truth.

-

She plays the saxophone.

-

Have you gone to the grocery store yet?

-

The explanations that researchers have thus far proposed are intriguing.

-

You really ought to spend time hiking in the Rockies.

To begin, we should emphasize that use of the is comparable to the act of pointing. This follows a long line of work on the semantics of the definite article (e.g., Hawkins, 1978; Lyons, 1999; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004), work that recognizes the as a signal to the hearer or reader that a referent is identifiable. In this sense, any meaningful explanation of the definite article must acknowledge the context of a speaker speaking to a listener or a writer writing to a reader.

Illustrating Context

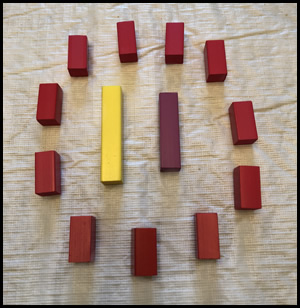

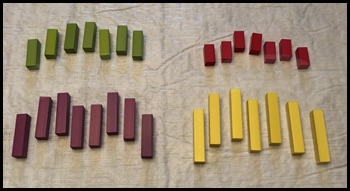

To illustrate the idea that the points within a context, try the following in-class task with Cuisenaire rods. Put out a set of rods (10 green, 1 purple, 1 black, 7 yellow) and ask students to point toward and then hand you “the purple block,” then “the black block,” and then “the yellow blocks” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Activity for illustrating pointing within context.

Students should have no trouble handing you the appropriate blocks. This is because each of the referents is uniquely identifiable within the context of the other blocks. Notice, if you ask for “the green block,” your students will struggle to fulfill your request. Because there are multiple green blocks, it is impossible to identify one unique referent. Change the request to plural (“the green blocks”) and your students will easily hand you all of the green blocks.

We can view use of the definite article as the speaker anticipating that the listener can successfully identify the referent. Unlike the rods in Figure 1, however, the context in which the referent is to be identified is not always physically present before the speaker and listener. One of the most challenging aspects of the definite article is determining the context in which a referent is to be identified (White, 2018).

When we say “the sun,” we are likely assuming unique identification from among heavenly objects visible in the earth’s sky (e.g., the sun, the moon, and the stars). We are not assuming an environment that includes heavenly bodies throughout the universe; after all, there are plenty of suns beyond our solar system. Thus, it may not be enough to give our students the aforementioned Rule 1. We should specify unique identifiability within an assumed environment.

Illustrating Unique Identifiability

Instead of solely relying on Rule 2 and telling our students that the is used because a noun has been previously mentioned in the text, we must go further and focus on meaning. Once a referent has been introduced within a story, that referent is presumed uniquely identifiable from among other referents in the story. Consider this beginning:

Once upon a time, there lived a king, a queen, and their many children. The king was known to…

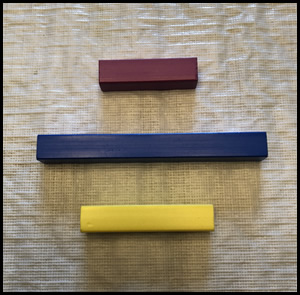

Through Cuisenaire rods (see Figure 2), we can show that readers are able to uniquely identify the king (yellow) from the queen (purple) and the children (red).

Figure 2. Once upon a time, there lived a king, a queen, and their many children.

In fact, this exact same set of rods could be used for the sun (yellow), the moon (purple), and the stars (red).

What about the sentence in example (a), “Please choose the best answer”? Instead of invoking Rule 3 to use the with superlatives, show students how the referent of a superlative form is uniquely identifiable. In Figure 3, we can identify the tallest block, just as we can identify the shortest block.

Figure 3.The tallest block and the shortest block.

Take a moment to revisit example sentences (b)–(g) and consider different ways to visualize how unique identifiability might be operating. In what environment or context is each referent being singled out?

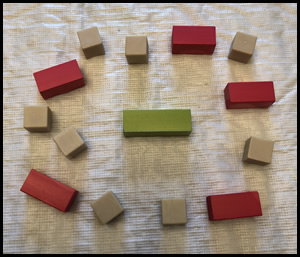

For (b), “They went to see a movie and were quite surprised by the ending,” it is common knowledge that movies (like many things) can be broken into distinct parts: beginning, middle, and end. The yellow rod below can be singled out as the ending.

Figure 4. They went to see a movie and were quite surprised by the ending.

For (c), “Be sure to tell the truth,” use of the definite article seems to presuppose there is one truth (green); yet, there may be a number of lies (red) or untruths (beige).

Figure 5. Be sure to tell the truth.

For (d), “She plays the saxophone,” it is not helpful to tell our students that the saxophone refers to one specific saxophone; rather, the relevant environment would include different types of musical instruments.

Figure 6. She plays the saxophone.

The green block is the saxophone, whereas, for example, the red is the trumpet, purple the guitar, black the piano, beige the flute. The same set of rods could be utilized to illustrate generic use of the definite article, such as with human groups, animals, body parts, plants, and human inventions (Larsen-Freeman & Celce-Murcia, 2015, p. 293). For instance, in the sentence, “the brain is an interesting topic of study,” different colored rods might represent different bodily organs.

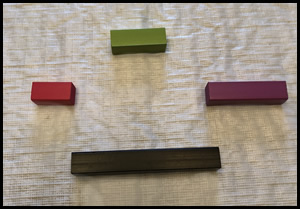

If (e), “Have you gone to the grocery store yet?”, is uttered in a conversation between two roommates, both speakers might have a particular store in mind. It is possible, however, that they shop at different grocery stores. In the latter case, a reasonable environment to construct for unique identification is a set of different service-oriented destinations across town, for example: the grocery store (black), the hardware store (purple), the bank (red), the post office (green).

Figure 7. Have you gone to the grocery store yet?

For (f), “The explanations that researchers have thus far proposed are intriguing,” learners might be tempted to suggest postmodification as the explanation for this use of the definite article. Here, the noun in question (explanations) is modified by a relative clause. This, however, is an unsatisfactory explanation, given that the same noun phrase is acceptable without the definite article (explanations that researchers have thus far proposed). It is not the postmodification of the relative clause itself that justifies use of the definite article; rather, the writer assumes that—with the postmodification—the reader has enough information to identify the referent. For example, we could construct the grouping of rods shown in Figure 8, where red rods represent explanations that researchers have proposed, green rods represent explanations that people other than researchers have proposed, and purple rods represent explanations yet to be proposed.

Figure 8. The explanations that researchers have thus far proposed are intriguing.

For (g), “You really ought to spend time hiking in the Rockies,” we could share the following rule with our students: Use the with names of mountain ranges (Larsen-Freeman & Celce-Murcia, 2015, p. 291). Though this guidance is undoubtedly helpful, we can go further. Just like in the previous examples, we can show how the underlying meaning of the definite article is consistent.

Figure 9. You really ought to spend time hiking in the Rockies.

Where the green rods represent the Rockies, the yellow might represent the Himalayas, the purple the Andes, and the red the Alps.

Student Independent Construction

After you have shared a number of examples, give your students more uses of the definite article and ask them to build their own representations with the rods. How would they explain the following? How would you?

h. We’re leaving on the next flight.

i. Have you ever gone swimming in the Pacific?

j. [At a jewelry store] Where are the watches?

Predicting appropriate use of the definite article through memorized rules-of-thumb will only get our learners so far. The, after all, is a tricky little word, and mastering its use is clearly no easy task.

Let’s try asking our students to focus on the meaning of the definite article and to find consistency across different uses.

References

Cole, T. (2000). The article book: Practice toward mastering a, an, and the (Revised ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). London, England: Hodder Arnold.

Hawkins, J. A. (1978). Definiteness and indefiniteness. London, England: Croom Helm.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Celce-Murcia, M. (2015). The grammar book: Form, meaning, and use for English language teachers. Boston, MA: National Geographic Learning/Cengage.

Lyons, C. (1999). Definiteness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

White, B. J. (2018). Making sense of the definite article through a pedagogical schematic. In A. Tyler, L. Huang, & H. Jan (Eds.), What is applied cognitive linguistics? Answers from current SLA research. New York, NY: de Gruyter Mouton.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Benjamin J. White, assistant professor and MATESOL Program director at Saint Michael’s College, holds a PhD in second language studies from Michigan State University. His research interests include pedagogical grammar, second language acquisition, and teacher development. He is particularly interested in the application of cognitive linguistics and sociocultural theory to language instruction. Ben is the current chair-elect of TESOL’s Applied Linguistics Interest Section.