|

Masako Maeda |

|

Kathy Strattman |

Finding contributory factors for enhancing communicative

competency continues to be a major interest and a challenge for ESL/EFL

instructors. Many thus far have concluded that the suprasegmental level

(stress, length, tone, intonation, overall rhythm, and timing), which is

collectively referred to as prosody, plays a more significant role than

the segmental level (consonants and vowels; e.g., Anderson-Hsieh, 1996;

Edwards & Strattman, 1996). The rhythm and timing of an

utterance created by emphasis or sentence stress in particular are

claimed to serve as signals to provide syntactic, semantic, and

discourse information to listeners, who attend to the stressed syllables

to determine essential information (Major, 2001). Is it possible to

create speech rhythm by adjusting the application of emphasis? Can this

adjustment be measured?

When speech is examined acoustically, stressed syllables are

produced with physiological force, which can be identified as longer

duration, higher pitch, or greater loudness in a perceptual dimension.

With the advent of computerized instruments, the auditory data of

duration, pitch, and loudness can be synthesized and analyzed

acoustically by means of time, fundamental frequency (F0), and

intensity.

Phonological Challenges to Japanese English Language Learners

The application of sentence stress to create a good speech

rhythm can be a major challenge for Japanese English language learners

(ELLs) when the total dissimilarities of the Japanese and English

languages are considered. Japanese is mora-timed. The mora is the

smallest unit of timing, all of which are pronounced with equal length

and loudness (Major, 2001). In contrast, English is stress-timed. The

durations between the primary stressed syllables are almost equal in

length regardless of the number of unstressed syllables in between. In

order to create the regular rhythm from stressed syllables to stressed

syllables, unstressed syllables are shortened by vowel reduction (i.e.,

schwa /ə/; Major, 2001).

Previous Studies

Anderson-Hsieh (1996) claims electronic visual displays show

little pattern differences between stressed and unstressed syllables of

Japanese ELLs compared to those of native English speakers (NESs).

Wennerstrom (1994) concludes that Japanese ELLs’ speech is without much

pitch variation or flat compared to NESs. Wennerstrom (2001) also argues

in her study of narratives that pitch is used most commonly to reflect a

speaker’s priorities to express emotions.

Statement of Problems

Although some findings indicate that Japanese ELLs demonstrate

less noticeable stress differences, few have provided objective evidence

using the acoustical measurements (i.e., vowel duration, F0, and

intensity).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate the Japanese ELLs’

ability to change speaking rhythms by applying sentence stress through

answering the following two questions.

- Is there a difference in the acoustic measurements of vowel

duration, F0, and intensity of the predetermined target words of the

scenario in the general reading between Japanese ELLs and

NESs?

- Is there a difference in these acoustic measurements between

Japanese ELLs’ first reading and second reading of the same scenario

with an additional instruction to apply feelings?

METHOD

Participants

The ELLs were 30 Japanese adults (15 males and 15 females) who

were born and raised in Japan and lived in Kansas, in the United States,

at the time of the study. Their ages ranged from 21 to 41 years, with a

mean age of 26.7 years for males and 32.8 years for females. Their

length of residence in the United States ranged from 1:00 (years:months)

to 15:07, with a mean length of 3:02 for males and 6:11 for

females.

The NESs were 30 Americans (15 males and 15 females) who lived

in Kansas at the time of the study and grew up in the Central Midland

region of the United States. They were age-matched with the Japanese

ELLs within a 2-year difference.

Reading Material

The reading material was a role-play scenario presented as a

voicemail message to a friend. See Table 1. The scenario included five

pre-determined target words for possible emphasis application to show

the speakers’ feelings. The words were all adjectives in

consonant-vowel-consonant combination. Both voiced and voiceless stops

and fricatives were used as well as /n/.

Table 1

Scenario

|

Situation:

You called your friend Jack to ask him a question, but he did not answer the phone.

So, you decided to leave him a message to call you back. You also decided to tell him again that you enjoyed the party he had a few days ago.

Hello, Jack. This is Kim. I have a question for you. Could you call me back? By the way, I had a good time at your party. It was hot outside. But, I met some fun people. You make the best spring rolls. I ate six of them. A big thanks to you. Bye. |

Note. Bold = target words. The target words in the actual narrative provided to the speakers were not in bold so that the speakers would not be influenced by any additional marks.

Procedures

Recordings. The participants’ speech samples

were recorded individually upon reading the scenario with the

instruction to read it as they would generally do. They were not told

which words to emphasize. Only the Japanese ELLs performed the second

task of reading with feeling.

Acoustic analysis. The target words of good, hot, fun, best, and six were

extracted from each sample using PRAAT software. The vowels of /ʊ/,

/ɑ/, /ʌ/, /ε/, and /ɪ/ in each target word were then measured for

duration (in ms), mean F0 (in Hz), and mean intensity (in dB) using

waveform and spectrogram.

RESULTS

Comparison Between Japanese ELLs’ and NESs’ General Readings

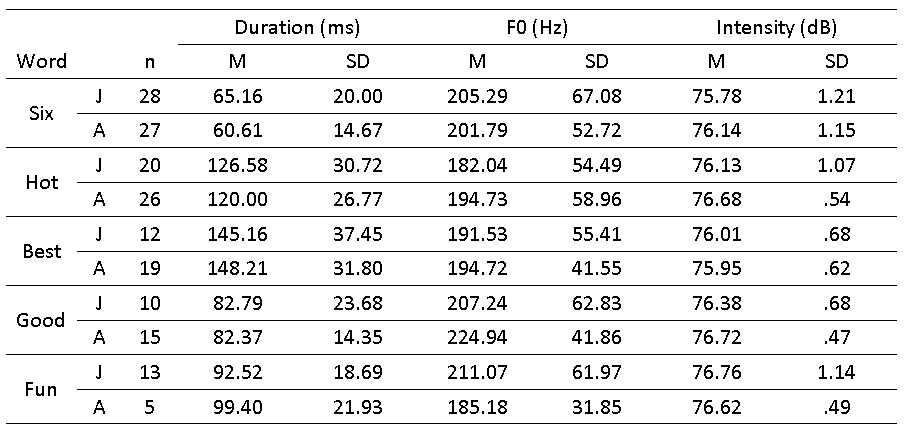

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics of the Three Variables in R1

for the Japanese ELLs and NESs for Each Target Word

Note. J = Japanese, A = American, n = 30 possible in each group, R1 = general reading.

A two-way MANOVA was conducted to evaluate the differences

between the Japanese ELLs and the NESs on the three dependent variables

of vowel duration, F0, and intensity of the target words in the general

reading. The two groups did not differ significantly in vowel duration,

F0, or intensity in comparison of the target words only. Table 2

summarizes the descriptive statistics of each word for the two

groups.

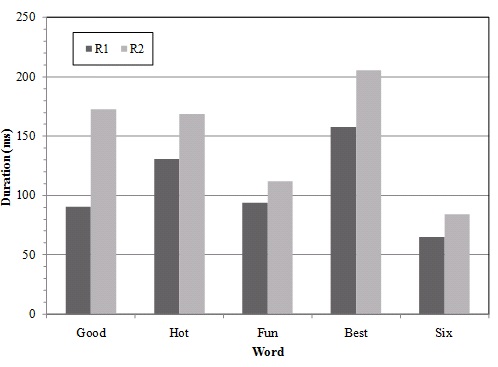

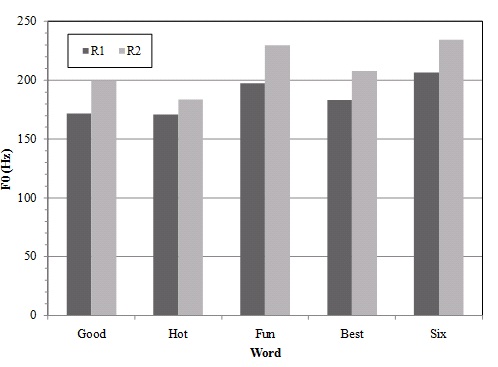

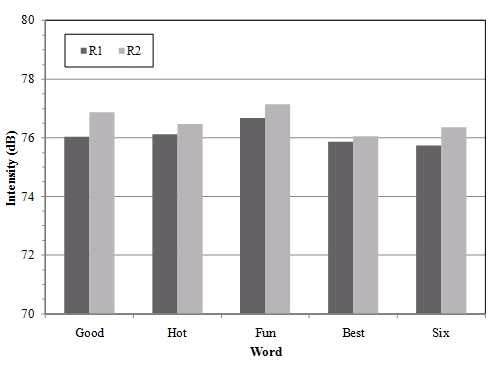

Comparison of the Japanese ELLs’ General Readings and Reading With Feelings

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the

effects of the two readings and the three variables (vowel duration,

F0, and intensity) on each target word within subjects and between

genders. There was a significant increase in the three variables on each

target word from the general reading to the reading with emphasis for

both genders. Overall results are as follows: F (1, 24) = 16.14, p < .05 for good; F (1, 17)

= 3.98, p < .05 for hot; F

(1, 13) = 36.32, p < .05 for fun; F (1, 16) = 16.91, p <

.05 for best; F (1, 24) = 16.14, p < .05 for six. Figures 1,

2, and 3 illustrate the overall changes in each acoustic variable for

the target words.

Figure 1. Duration differences from R1 to R2 (the second reading)

in the target words for the Japanese ELLs.

Figure 2. F0 differences from R1 to R2 in the target words for

the Japanese ELLs.

Figure 3. Intensity differences from R1 to R2 in the target words

for the Japanese ELLs.

DISCUSSION

Comparison Between Japanese ELLs’ and NESs’ General Readings

No significant difference was found in vowel duration, F0, and

intensity of the target words between the Japanese ELLs and the NESs.

The results contradicted Wennerstrom (1994), who found that English

productions by Japanese ELLs demonstrated little prosodic variations,

most specifically regarding the pitch variation. It could be inferred

from the current findings that the Japanese ELLs in this study did apply

emphasis to create a rhythm without instruction to do so, which was

similar to the NESs in the study.

The difference in the current results may be related to a

change of focus in pronunciation instruction from the segmental to the

suprasegmental level to improve communicative competency. It could also

be caused because of the modern era of globalization, which provides

more opportunities to communicate with NESs and to hear English

spoken.

Further examination of the mean differences in each acoustic

variable indicates that the vowel duration of the Japanese ELLs, as a

whole, was slightly longer than the NESs, although the F0 was lower and

the intensity was smaller. These findings are also in contrast to the

findings by Wennerstrom (2001) that emphasis is most commonly addressed

by pitch to add information to an utterance.

Comparison of the Japanese ELLs’ General Readings and Reading With Feelings

The statistically significant changes from the first reading to

the second reading demonstrate that the Japanese ELLs were capable of

adjusting duration, F0, and intensity of the vowels by applying

emphasis. The results confirm that they made overall changes most in

duration, then in F0, and in intensity, which is consistent with the

outcomes of the first question that the Japanese ELLs’ overall vowel

duration was longer than the NESs even though nonsignificant.

The variable they used most to apply varied emphasis was not

F0, contrary to Wennerstrom’s (2001) study. Even though the Japanese

ELLs could make changes in the three variables, the finding that

duration was used more for emphasis could be attributed to the mora

system in the Japanese language, which might remain as an overriding

influence.

Implications and Future Research

The findings provide an encouraging starting point for

enhancing nonnative English speakers’ communicative competency by

showing the potential for change. The advancement of technology has

increased opportunities for global communication. Young adults in this

study appear to have taken advantage of technology and current

instructional approaches, which focus more on suprasegmental and

conversational aspects.

In the current study, the application of emphasis was thought

to be an important contributor for communicability. However, the

question remains: Does applying emphasis itself help enhance

communicability, or is communicability enhanced only when emphasis is

appropriately used?

Also, investigation of the relationship between the ability or

willingness to apply emphasis and other factors, such as age and length

of residence in the United States, may reveal additional noticeable

outcomes. Moreover, the use of human ears as measurement tools to

investigate the relationships between comprehensibility and application

of emphasis should be explored.

REFERENCES

Anderson-Hsieh, J. (1996). Teaching suprasegmentals to Japanese

learners of English through electronic visual feedback. JALT

journal, 18, 315–325.

Edwards, H. T., & Strattman, K. H. (1996). Accent modification manual: Materials and activities.

San Diego, CA: Singular.

Major, R. C. (2001). Foreign accent: The ontogeny and

phylogeny of second language phonology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Wennerstrom, A. (1994). Intonational meaning in English

discourse: A study of non-native speakers. Applied

Linguistics, 15, 399–420.

Wennerstrom, A. (2001). Intonation and evaluation in oral

narratives. Journal of Pragmatics, 33, 1183–1206.

Dr. Masako Maeda is a lecturer in the Department of

Curriculum and Instruction at Wichita State University, where she

teaches linguistics. Her areas of interest include ESL pronunciation,

foreign accent modification, phonetics, and applied

linguistics.

Dr. Kathy Strattman is an associate professor in the

Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at Wichita State

University. As a certified speech-language pathologist, she has taught

university courses in accent modification for ELLs and is the coauthor

of the Accent Modification Manual. |