|

When I began teaching high school English in 2001, many veteran

educators graciously offered me their classroom materials, their

professional and personal support, and their guidance. But no piece of

advice stands out more than the suggestion I heard most frequently: that

because educational trends, theories, and mandates come and go, I

should ignore all the noise, decide what I knew was best for my

students, and “just close the door and teach.” Doing so, as I understood

it, would be both act of self-preservation and a way to protect my

students from outside forces that were thought to have no place in the

classroom. And though I agreed with and subscribed to this advice early

on in my career, I recognized, fairly quickly, just how flawed a message

it really was—and how much of a disservice we do to teachers and

students if we ignore the ways in which social and political issues and

education are inextricably linked.

The current political climate in the United States, which has

exposed many Americans’ overt hostilities toward issues of social

justice, has compelled me to reflect even more—beyond an academic

sense—on my students’ diverse backgrounds and needs, and on the extent

to which social justice issues affect our everyday environment, and on

my own identity.

My father is, as far as he knows, of one hundred percent Irish

descent, and my mother, as far as she knows, is of one hundred percent

Armenian descent. Since both these ethnicities have embedded in their

genes legacies of historical injustice and oppression, I am particularly

attuned to these matters—but it is the Armenian side that is occupying

my thoughts, these days, since my mother, Susan Arpajian Jolley, and my

uncle, her brother, Allan Arpajian have published an incisive and moving

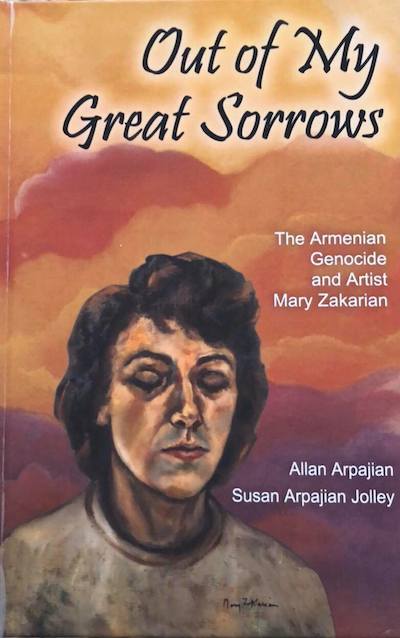

account of the Armenian situation in a book entitled Out

of My Great Sorrows: The Armenian Genocide and Artist Mary

Zakarian (Routledge, 2017).

The book’s cover art is Mary’s self-portrait.

Mary Zakarian is my great aunt, my grandmother’s sister:

practically part of my immediate family. This book, which combines

biography, history, and memoir, has given me new insight into the

painful legacy of the Armenian people, who to this day are seeking

justice for, and acknowledgement of, a genocide perpetrated a hundred

years ago in the Ottoman Empire. As the authors, Arpajian and Jolley,

write in the introduction to their book, “the political and

psychological effects of this event remain an open wound to descendants

of both victims and perpetrators despite the passage of time” (xv). Lest

anyone question why a hundred-year-old event has significance to us

today, consider this 1939 statement by Hitler to his generals,

justifying the invasion of Poland: “Accordingly, I have placed my

death-hand formations in readiness—for the present only in the East—with

orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion,

men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus

shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who,

after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the

Armenians?” (Berger, 2002, p. 166, emphasis added) To this

day, the Armenian Genocide remains unacknowledged by the Turkish

government (Hovannisian, 2003, p. 2), and this is precisely the reason

why we must actively seek to identify and prevent injustice on a global

scale.

For those who are unfamiliar, the Genocide of 1915 was an

instance of ethnic cleansing in which a million and half Armenians were

either murdered, tortured, and sent on death marches into the Syrian

desert, at the direction of the Ottoman regime (Peroomian, 2012). The

political situation at the time was complex, as the Ottoman Empire was

crumbling, World War I was breaking out, and nationalism was on the rise

world-wide. (For a comprehensive explanation of the situation see

Akçam, 2006.) But Arpajian and Jolley distill the

situation into understandable terms for non–historians, and also explain

how easily, under certain conditions, injustices of the worst sort can

be perpetrated.

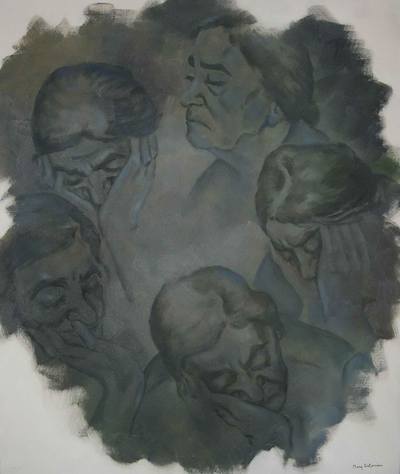

Zakarian considered “My Mother’s Endless Lament” (oil

on canvas, early 1970s), which represents the never-ending suffering of

the genocide survivor, to be her most important work.

At the heart of this book is the legacy of trauma. My great

grandmother, Mary’s mother, Arek Zakarian, suffered unimaginable losses

and abuse from the time of the genocide, in 1915, until she was able to

find safe passage to the United States in 1923. During those eight long

years, Arek witnessed the murder of her husband and the beheading of her

two small sons, ages two and four. She wandered through a wasteland,

subjected, as are all women in genocide, to sexual abuse. It is no small

victory that she survived and was able to remarry in America and raise a

second family. While Out of My Great Sorrows devotes

one chapter to Arek’s story, and another to my great grandfather, Moses

Zakarian, who suffered his own losses, the focus remains on Mary, a

sensitive child who grew up under the shadow of the Genocide and her

mother’s suffering. As the book explains, posttraumatic stress disorder

affects not only the survivor or trauma, but also succeeding

generations. While Arek remained largely silent about her experiences,

her children inherited her trauma nevertheless. The authors cite the

chapter from Plight and Fate of Women During and Following

Genocide in which Rubina Peroomian states that horrifying

memories “remain alive in the next generation and the one after that”

(18).

While Out of My

Great Sorrows examines Mary Zakarian’s artistic development

and showcases her powerful portraits of her parents and her vibrant

still life studies, it is the examination of Mary’s psyche that is most

compelling. In Philadelphia during the Great Depression, she and her

family suffered not only monetary poverty but also psychological

difficulties brought on by the fact that they were refugees of war and

genocide. Mary herself experienced survivor guilt, the feeling that her

own pleasure and happiness was a betrayal to her mother’s pain. She

harbored ambivalent feelings about her mother, which led her to question

her own worth and her religious faith. She had difficult relationships,

suffered from agoraphobia, hypochondria, and generalized anxiety. All

these conditions are symptoms of PTSD, and not unlike symptoms of actual

survivors.

Nevertheless, Mary was a successful artist and beloved teacher.

Formally trained at Moore College of Art and Design and Pennsylvania

Academy of Fine Arts, she started her own art school, the Zakarian

School of Art, in her studio in Philadelphia in 1971. She exhibited her

work on the east coast and sold hundreds of paintings in her lifetime.

Later in her life, she became an advocate for genocide awareness,

speaking on the topic and relating her family’s story and its

psychological impact on her art. While her successes were gratifying,

she remained mired too much of the time in depression and anxiety. The

authors of Out of My Great Sorrows are clear in

explaining that one cause of Mary’s difficulties was her innate

temperament, but that much can also be attributed to the unresolved

issues of oppression, injustice and grief of the Armenian

people.

Mary specialized in portraits of oppressed, marginalized, and

disenfranchised people. Leaving this legacy in her art clearly shows her

own concern with social justice. As the authors write in a chapter

entitled “Celebrating Everyman, “She portrayed a virtual rainbow of

humanity…Her art expresses the transience of earthly life and yet the

simultaneous permanence of the spirit” (166). Their last chapter

evaluates the role of tragedy and trauma on her work: “The Armenian

Genocide, the propulsive force at the source of Zakarian’s art, is a

psychic wound that will not heal…But the catastrophe—not just of 1915

but the entire history of this ‘nation’—like anything negative in human

experience, is both a destroyer and a creator. An oppressed and

victimized group’s wish, whether conscious or not, is that the suffering

endured will make them greater than they would have been in its

absence...This, in a nutshell, is tragedy on the vast stage of history.

Man is beaten but is somehow superior to the forces that have brought

him down” (183).

Needless to say, I have known my Aunt Mary all my life—and the

primary identity I will always assign to her is that of a loving aunt.

However, this book has helped me understand her, my family, and the

legacy of people who have suffered massive injustice. Perhaps most

importantly, it has served as a reminder that we cannot successfully

educate our children if we “just close our doors” to the injustice that

plagues our world. By studying the psychology of survivors of trauma,

whether they be Armenian, African American, Irish, Jewish, or any of the

myriad other ethnicities who have suffered oppression and injustice,

educators and students can gain understanding of other people and of the

world—and we, as educators, can better understand our students, their

diverse needs, and the critical place that issues of social justice have

in our classrooms. In this regard, Out of My Great Sorrows:

The Armenian Genocide and Artist Mary Zakarian can aid us in

the pursuit of social justice.

References

Akçam, T. (2006). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Arpajian, A. & Jolley, S.A. (2016). Out of My

Great Sorrows: The Armenian Genocide and Artist Mary Zakarian. New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers.

Berger, R.J. (2002). Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach. New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers.

Hovannisian, R.G. (2003). Confronting the Armenian Genocide. In R.G. Hovannisian (Ed.), Looking Backward, Moving Forward (pp. 1-7). New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers.

Peroomian, R. Women and the Armenian Genocide. (2009). In Totten, S. (Ed.), Plight and Fate of Women During and Following Genocide (pp. 7-24). New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers.

Ani McHugh is a high school English teacher in Delran,

New Jersey. She holds a B.A. in English from Ursinus College and an

M.Ed. from East Stroudsburg University. |