|

Keith M. Graham

|

|

Yunkyeong Choi

| Introduction

Today’s world is filled with tension. Newspapers tell of

suicide because of sexual orientation, ethnic and religious genocide,

and racial violence. Though many voices are suggesting that “diversity

is one of our greatest strengths to be celebrated” (Slattery, 2012, p.

149), it seems that rather than celebrating, the world is eradicating

it. The evidence is clear; something needs to change, and we believe

change can begin with the English language teaching (ELT) curriculum and

the literature we bring into our classrooms. In the paragraphs that

follow, we will propose a model for a postmodern diversity curriculum

and the challenges and opportunities for implementation.

Postmodern Diversity Framework

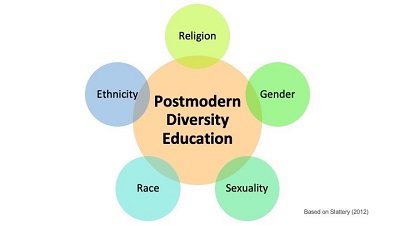

Our postmodern diversity framework is based on the work of

Slattery (2012). The framework is made of five dimensions that we

believe educators at all levels should include in their curriculum:

religion, gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity (Figure 1). Beginning

with the first dimension, religion, it is no secret that many

curriculums do one of two things—either try to eliminate religion from

the curriculum altogether or teach one religion exclusively. We approach

religion from the perspective that learning religions can be a conduit

for a deeper understanding of one’s self and the world around them.

While we believe religions, as a single subject, can help students learn

about themselves, integration of all religions into other school

subjects allows for a richer understanding of the world. For example, a

history teacher could have students speak about historical events from

the perspective of various religious groups.

Figure 1. Five dimensions of the postmodern diversity framework

Gender and sexuality are two topics also often avoided in K-12

schools, and this suppression is causing suffering (Slattery, 2012).

First, it is important to understand that gender is a psychological

trait and sex is a biological one (Newman, 2018). As such, various

combinations beyond the traditional heterosexual male and female exist.

Additionally, there are many misunderstandings in society about the

interrelationship between gender roles, sexual behavior, and sexual

orientation due to common interchangeable uses of these terms, which

often remain unchallenged and undiscussed (see Slattery 2012 for a full

discussion of these concepts). These misunderstandings have grave

consequences for our students and communities. “There remains intense

pressure on people to conform to traditional norms...Some find it easier

just to go along with the expectations rather than fight for

alternative preferences or desires” (Slattery, 2012, p. 158). To make

educational environments more inclusive of the wide range of genders and

sexual orientations of students, literature featuring these diverse

groups should be incorporated into the curriculum. A good resource for

literature with characters of diverse genders and sexualities are the

lists provided by Common Sense Media (2019) and the Anti-Defamation

League (2019).

Race and ethnicity are perennial issues in our world and are

arguably the topics which get discussed more often in schools than the

other dimensions listed above. However, we believe two things remain

missing from conversations about race and ethnicity in classrooms.

First, the discussion is often about “others” rather than self. Slattery

(2012) tells us, “racial [and ethnic] issues in the postmodern

curriculum emphasize investigations of the self and conceptions of the

self in relation to the other” (p. 174). We must understand our own race

and ethnicity before we can understand others. Second, as Kubota and

Lin (2006) note, “TESOL has not sufficiently addressed the idea of race

and related concepts” (p. 471), and the authors call for more discussion

of race, both in ELT research and classroom practices.

Challenges

While we believe including the dimensions of religion, gender,

sexuality, race, and ethnicity in the curriculum and literature we use

can help bring powerful change to the world, we also recognize that

implementation brings many challenges. Below we examine some potential

challenges first by looking at what current ELT materials offer on these

topics and then turning toward challenges for teachers and schools

through the lens of the South Korean context, where the second author

has worked as an English teacher. This focus on one context serves to

highlight the challenges that exist in implementing a postmodern

curriculum.

Current ELT Materials

We chose one of the most widely-used ELT materials around the

world, Oxford Bookworms Library, and analyzed some of its titles using

the postmodern diversity framework. We will present an analysis of level

four (intermediate level) for this example. In level four, out of a

total of 30 graded readers we found that only five of them address

issues of race and ethnicity. For example, there were two texts related

to race (i.e., Gandhi and Nelson Mandela) and three books on ethnicity

(i.e., A Time of Waiting: Stories from Around the World, The Price of

Peace: Stories from Africa, and Land of my Childhood: Stories from South

Asia). However, we found no books addressing issues of religion,

gender, or sexuality. The stories in other levels were very similar with

very few books addressing aspects of postmodern diversity. Rather,

there were quite a few books which reflected traditional Western images,

particularly those of typical Western middle-class society and

stereotypical gender roles. From this, we can conclude that there seems

to be a gap between our postmodern diversity curriculum and our current

ELT materials.

Local Challenges from the South Korean Perspective

As many teachers would agree, there are clearly some challenges

beyond materials for implementing a postmodern ELT curriculum

internationally. Based on the second author’s experience, these

challenges of implementing a postmodern curriculum is particularly true

in South Korea. First of all, religion is a topic that is considered a

private matter in South Korea and not something that should be discussed

in school settings. As some may know, South Korea has a test and

content-focused school curriculum. Subjects that are directly related to

the college entrance exam (e.g., math, English, language arts) make up

the most important part of the curriculum and other

subjects (e.g., music, arts) tend to be considered as trivial. As a

result, there is rarely time for robust discussions on issues that are

outside of the curriculum such as religion.

In addition, the number of people who identify with a religion

has been continuously decreasing, particularly among young adults.

According to a survey conducted in 2017 by the National Council of

Churches in Korea, only 46.6% of Korean adults reported having a

religion, and among the population aged between 20 to 29, only 30.7%

were reported to have a religion (Yu, 2018). Due to these changes, it

seems like it is particularly difficult for teachers to address issues

of religion in their classrooms.

Next, gender and sexuality issues are considered as taboo

topics in South Korea. Sexual diversity is not accepted culturally, and

conversations on homosexuality, transgender, or intersex are not

accepted in schools. As these issues are not properly addressed in the

school curriculum and students are not educated on these topics, many

students are unaware of the fact that there are diverse gender

populations beyond the male/female dichotomy and people with different

sexual orientations. Furthermore, many often end up finding

inappropriate or biased information from the media or Internet, leading

to misinformed views on gender and sexual diversity.

Finally, South Korea is an ethnically and racially homogeneous

country so people believe that discrimination due to race or ethnicity

is not an issue. When they think of racial or ethnic discrimination,

they think about racial discrimination in the U.S. or issues of European

colonialism around the world and believe it is a topic of the past.

However, it is a real issue in South Korea that often goes unnoticed.

For example, there are many foreign workers from developing countries

and the number has been increasing continuously. In 2017, there were

1.28 million adult immigrants (over 15 years old) in Korea and most of

them were foreign workers (0.9 million) (Korea National Statistics

Office, 2017). Many of these foreign workers work long hours and receive

pay below the minimum wage due to employers taking advantage of

workers’ lack of Korean-language proficiency and misunderstandings about

labor laws, which is clearly an act of discrimination against people

with different racial and ethnic background. These workers are faced

with discrimination not only in their workplaces, but also in their

everyday lives. Moreover, children from these multicultural families

have a hard time adjusting to their school, and the schools are failing

to incorporate these issues in their curriculum. We believe that most of

this discrimination seems to be caused by the lack of properly

addressing these issues in school curricula, where students, both South

Korean and expat, are not educated on them. Critically examining

curricula from a postmodern perspective and implementing changes to

instruction for South Korean students that are inclusive of all

postmodern dimensions may lead to the raising of student awareness about

diversity issues within their communities.

Opportunities for Implementation

Given the great challenges discussed, a radical change in the

curriculum toward one inclusive of postmodern diversity may seem

unfathomable. However, we feel the ELT community, more than any other

field of education, has a unique opportunity to implement a postmodern

diversity curriculum around the world. The opportunity begins with all

ELT teachers becoming educated on the dimensions of postmodern

diversity. Teachers must recognize that the modern categories of

religion, gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity do not fit this

postmodern world and do not represent many of our students. In addition,

teachers need to also recognize biases created by modern notions and

learn to love and defend all people. Reading texts on incorporating

diverse curricula, such as Slattery (2012), or taking courses informed

by critical race, gender, or queer theory will help raise teachers’

awareness of diverse populations and issues of systemic inequality. Once

we have educated ourselves, the next step is to educate our colleagues

as it is important that we approach postmodern diversity together as one

educational community.

Once the ELT community is informed, we can then begin to

educate our students. We believe the best way to engage students in

these conversations is through literature. However, as seen above, our

typical ELT materials fall short, so teachers will need to look beyond

typical curriculum sources. There are many books that address the five

dimensions of postmodern diversity. One book addressing sex and gender

is Alex as Well (Brugman, 2013), a story of an

intersex person searching for an identity. The Name

Jar (Choi, 2001) is a great book for addressing race and

ethnicity, telling the story of a Korean girl struggling with her Korean

name in the United States. The Anti-Defamation League (2019) is a great

resource for finding books that can be made accessible for language

learners through teacher support and can inform students on postmodern

diversity issues. We also hope that as more classrooms teach postmodern

diversity, ELT publishers will be encouraged to produce materials more

inclusive of each of the dimensions of the postmodern diversity

framework.

Conclusion

We have a rare opportunity as a world network of ELT teachers,

not limited by any borders, to make worldwide change. The ELT curriculum

can truly be the catalyst for change that eliminates the tensions of

the world. While the ideas of this article may seem dangerous to some,

we would like readers to keep in mind the words of Michel Foucault,

“everything is dangerous, nothing is innocent” (Foucault, 1980, p. 33).

Ignoring these ideas may be as dangerous as reading them. With that in

mind, we challenge the ELT community to begin including postmodern

diversity issues in your language teaching curriculum.

References

Anti-Defamation League. (2019). Books matter: Children’s

literature. Retrieved from

https://www.adl.org/education-and-resources/resources-for-educators-parents-families/childrens-literature

Brugman, A. (2013). Alex as well. New York: Henry Holt.

Choi, Y. (2001). The name jar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Common Sense Media. (2019). LGBTQ books. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/lists/lgbtq-books

Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings (pp. 1972–1977). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Korea National Statistical Office. (2017). Foreign

worker employment rate [Data file]. Retrieved from

http://www.kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/3/4/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=365286&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt=

Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2006). Race and TESOL:

Introduction to concepts and theories. TESOL Quarterly,

40(3), 471-493.

Newman, T. (2018). Sex and gender: What is the difference? Medical News Today. Retrieved from

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/232363.php

Yu, J. (2018, January). Decrease in Korean population with a

religion. The Korea Times. Retrieved from

http://www.koreatimes.com/article/1096127

Keith M. Graham is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in

curriculum and instruction. He holds a master’s degree in education from

Sam Houston State University. His research interest is international

English teaching, particularly English Medium Instruction and Content

and Language Integrated Learning.

Yunkyeong Choi is a Ph.D. student in Curriculum and

Instruction with a specialization in English as a Second Language. She

holds a master’s degree in English Education from Hanyang University in

Korea. Her research interests include task-based language teaching

(TBLT), particularly how TBLT could be used to promote L2 learners’

pragmatic development.

|