|

“We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience” (Dewey, 1933).

In education, reflective practice has long been recognized as

one of the core foundations of the profession (Dewey, 1938; Schön, 1983;

Jay & Johnson, 2002; Farrell, 2013, 2015).

This study examined reflective practice as part of the

professional development program for experienced EFL teachers in the

Israeli Ministry of Education (MOE) framework.

In the courses, reflective journals were kept by the

participants as a tool for self-evaluation and for contemplation of the

implementation of newly acquired skills in subsequent teaching. This

article draws on the qualitative dataset of these reflective journals.

In our mixed-methods study, we evaluated the teachers’ input with the

aim of tapping into their learning processes as well as into their

attitudes towards reflection. We enquired into what and whom teachers

focus their reflections on, in addition to purposes of journal keeping

(Moon, 1999). Moreover, we measured the level of reflective thinking

along the lines of Kember et al. (2000, 2008).

The Background

Professional development of EFL teachers in Israel is carried

out in a top-down manner (Farrell, 2013): 30-hour courses on various

topics are offered under the supervision of the MOE. The taking of two

courses per year is mandatory for all teachers in the public sector.

The content of the course this study is based on focused on

alternative assessment strategies, and incorporated material developed

by the British Council. Participants in professional development (PD)

courses have varied teaching experience of 1 to 20+years. The course

under discussion offered teachers an opportunity to enrich their

professional expertise by using novel alternative assessment strategies

in language education. The topic of the course did not play a

significant role in our research, as we were interested in generally

assessing the significance of reflection.

The Action

Our action of incorporating reflection into in-service training

courses arose in order to make the learning process more efficient. Our

goals were the following: to create a process that would help

participants internalize the course material; and to prompt thinking

about ways of implementing their newfound methods and skills.

Furthermore, to provide the instructor with an insightful tool for

monitoring learners’ progress and to develop a method of evaluation as

to whether the material covered in the course was in fact, transferred

into classroom practice.

Reflective journals were kept by all 23 participants as a tool

for self-evaluation and contemplation. The teachers were required to

engage in end-of session reflective writing on the absorption of new

knowledge and its significance for own teaching context.

We then analyzed the teachers’ input of a total of 82 responses.

The Study

The rationale of this study was to evaluate the significance of

the reflective process. Our approach was two-pronged: explore the foci

and the depth of the participant’s reflections; and teachers’ attitudes

towards the tool of reflection itself.

Our research questions were:

1. What did the participants’ reflections focus on?

2. Who was participants’ reflections focused on, i.e. did they

express themselves more as learners or as teachers?

3. Which purposes of journal keeping were met? (Moon, 1999)

4. How deep were the participants’ reflections? (Kember et al. 2000, 2008)

Methodology

The dataset we used to consisted of: teachers’ reflective

journals, lecturer reflections, and an end-of-course questionnaire. The

data collection involved two phases: end-of-session reflections and an

end-of-course questionnaire. The first phase lasted for 8 sessions,

spread out over approximately 3 months. At the end of each session, 20

minutes was allocated for reflective writing prompted by questions such

as:

· What new information have you learnt today?

· What insights did you gain today?

· What changes can you make to your teaching as a result of what you have learnt from the session?

· How do you think you can implement these changes?

The second phase involved an overview of participants’ experience with reflection as a tool.

We carried out critical discourse analysis on Faucaltian lines,

targeting how teachers in the setting of PD understand their teaching

practice in the light of new material. The mixed-methods study employed

discourse analysis on Faucaltian lines, targeting how teachers in the

setting of PD understand their teaching practice in the light of this

recent training. In particular, we employed Gee’s (1999) model of

Discourse.

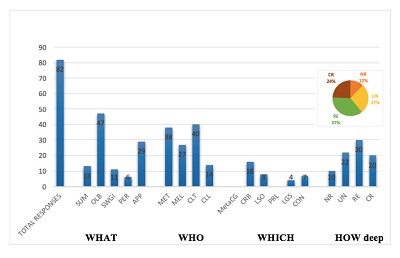

The responses were examined for emerging themes predetermined

according to our research questions. We analyzed our data in a

qualitative-interpretive and a quantitative manner. For a detailed

break-up of our criteria see the graph below.

Findings

Responses indicate that reflection contributes considerably to

the internalization of course content and the application thereof in

classroom practices. Teachers value the significance of the tool both as

learners (review, summary, higher levels of involvement), and as

teachers (adopting the tool into their own classroom practices). In

following paragraphs, we discuss selected findings. Figure 1 illustrates

our comprehensive results.

Our findings indicate that while teachers took both

learner-centered and teacher-centered perspectives when focusing on

enriching their professional expertise, their reflections were

predominantly on their own learning behaviors and performance evaluation

rather than on classroom implementation. 38 out of the 82 responses

included as “me as a teacher”–minded comments, such as“It made me think

about different tasks I can do with my classes”; 27 were focused on “me

as a learner,” for example, “Today I realized that summarizing isn’t as

easy as I thought, it includes different points and I really improved my

summarizing skills.” Some did not include any clear-cut references to

any of these categories.

47 of the responses were of “own learning behavior”-type, such

as, “I also learned some new ways I can use to introduce a text or work

on a text even if it's boring” or “I enjoyed the pyramid reflection

because it made me think about additional information even when it

seemed very difficult”; though only 29 included explicit reference to

future applications, like “I take some of them [ice-breakers] to my

classes, for the beginning of the year activities” or “I got some ideas

how to use this wonderful and so up to date tool in my

classes.”

According to the data, only a small number of responses

explicitly reflects the purposes of journal keeping. Similarly, only 29

of 82 mention explicit application of course content to classroom

practice.

A definitive pattern of journal-keeping purposes did not emerge

from the teachers’ writing as the low number of results on this

criterion demonstrates. The three most dominant purposes indicated were:

(1) critical review of strengths, weaknesses, learning and teaching

styles and strategies; (2) learning of self and others; and (3)

exploring connections between knowledge learned and their own ideas

about that knowledge.

The lack of clear-cut references to our target items could

generate from the fact that reflection was novel exercise for the

participants to attempt and they were not used to prospective and

predictive reflection in the setting of PD.

Another puzzling finding concerns lower levels of reflection:

39% of the responses were of the non-reflection and understanding type.

The latter two findings prompt further action in how to maximize the

effectiveness of the reflective tool in PD. Teacher educators could bare

this in mind when designing PD courses.

Figure 1. The foci and depth of reflections

APP=application; CLL=classroom learning; CLT=classroom

teaching; CON=explore connections between knowledge learned and own

ideas about that knowledge; CR=critical reflection; CRB=critical review

of behaviors; learning and teaching styles; LGS=set and track learning

goals; LSO=learning of self and others; MEL=me as a learner; MET=me as a

teacher; MetaCG=metacognition development; NR=non-reflection; OLB=own

learning behavior/process; PER=own performance in the session;

PRL=product of learning; RE=reflection; SUM=summary of content; SWGI=

critical review of strengths, weaknesses, good with, have to improve;

UN=understanding.

Our results have shownthat the predictive reflection exercises

are yielding enhanced energy among the participants. Furthermore,

reflection serves the instructor as an in-course monitoring device.

Teachers value the significance of the tool both as learners claiming

that reflection “makes me rethink about my learning and then enables me

to process better what I've learned,” and as teachers adopting the tool

into their own classroom practices. They report a highly positive

influence of the reflective practice on future application of course

materials: on a scale of 1–5, 33% gave the score 3, 38% gave the score

4, and 27% gave the score of 5.

The Impact of Reflection on Professional Development Programs

From the data, we found that reflection contributes

significantly to PD and aids prospective practice. It benefits teachers

as learners and educators, and subsequently offers a tool that can be

used with students. For the instructor, reflection serves as a source

for feedback, evaluation and input for future development.

How can we further explore the effectiveness of reflection as an essential component of PD?

One possible avenue is teacher identity: our early findings

reveal notions of ideal, ought-to and feared selves. Written reflection

facilitates investment in professional development since it grants an

opportunity for teachers to examine their professional raisons d'être

and “provide insight into who they are as teachers” (Cirocki &

Farrell, 2017). In future research, we intend to investigate the

exposition of language teacher identities and possible selves in the

framework of Possible Language Teacher Self theory (Kubanyiova, 2009).

References

Ciroki, A., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2017). Reflective

practice for professional development of TESOL practitioners. The European Journal of Applied Linguists and TEFL,

6(2), 5–24.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the

relation of reflective thinking to the educative process.

Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery.

Dewey, J. (1938). Education and experience. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2013). Reflective practice in ESL

teacher development groups: From practices to principles.

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Farrell, T.S.C. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection

in second language education: A framework for TESOL

professionals. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, P. (1999). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis:

Theory and Method. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jay, J. K., & Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing

complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18,

pp.73-85.

Kember, D., Leung, D.Y.P., Jones, A., Loke, A.Y., McKay, J.,

Sinclair, K., Tse H., Webb C., Kam F., Wong Y., Wong M. & Yeung

E. (2000). Development of a questionnaire to measure the level of

reflective thinking. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, 25(4), 381–395.

Kember, D., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., & Wong, F.K.Y.

(2008). A four-category scheme for coding and assessing the level of

reflection in written work. Assessment & Evaluation in

Higher Education, 33(4), 369–379.

Kubanyiova, M. (2009). Possible Selves in Language

Teacher Development. In Dörnyei Z. and E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self (pp.

314-332)Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Moon, J.A. (1999). Learning journals: A handbook for

reflective practice and professional development. Abingdon,

UK: Routledge.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How

professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic

books.

Bridget Schvarcz is a PhD candidate in linguistics

at Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan Israel and a teacher educator for the

Israeli Ministry of Education, Department of Professional Development of

Teaching Staff. She is the vice-president-elect for the English

Teachers’ Association Israel, an affiliate to TESOL. Bridget teaches

in-service training courses on various topics for experienced EFL

teachers across the country. Her research interests are formal

semantics, educational linguistics, EFL teacher education, and language

teacher identity. Her combined expertise in these fields has led her to

design courses and conduct studies which integrate theoretical knowledge

with classroom practice. |