Reducing Learner Anxiety With 5 Mindfulness Techniques

by Saghar Leslie Naghib

Many multilingual learners of English face stress and/or

anxiety, not just about learning a new language but also about their personal

narratives—the aspects that rest beneath the surface of what they might

demonstrably show. Though adopting a mindfulness practice in the classroom can

take place at any point, doing so at the beginning of a new year provides an

ideal opportunity to develop new habits and implement practical techniques that

can leave a lasting impact on one’s learning experience. As an English language

lecturer and conflict resolution practitioner, and with the perspective that

pedagogy and practice inform each other, I suggest approaching the issue of

student stress and anxiety with five mindfulness techniques:

- Gradual exposure

- “I feel” statements

- Four elements of stress reduction (Shapiro,

2012)

- Self-scan, awareness, and containment

- Reframing automatic negative thoughts (ANTs;

Amen, 2015)

Note: It is well worth noting

the adage, “One cannot pour from an empty cup.” Check in with yourselves first

and make sure your proverbial cup is filled—enough that you can pour out for

your students. (Of course, this directive is easier written than done, in

practice.)

Because stoicism is often both a geographical and

academic cultural norm, prioritizing and modeling practical methods for mental

health inclusivity supports a classroom environment that truly teaches the

whole person.

The framework for these techniques should be led

with the following motto: Progress over perfection. Normalizing conversations

about stress and anxiety in the classroom promotes and sustains a learning

environment where students prioritize their well-being in relation to learning.

It is most effective to introduce the following techniques as early as the first

few weeks of your academic context, but it is beneficial at any time.

For each technique, I've provided guiding

objectives and principles so you can adapt the techniques to your audience and

level.

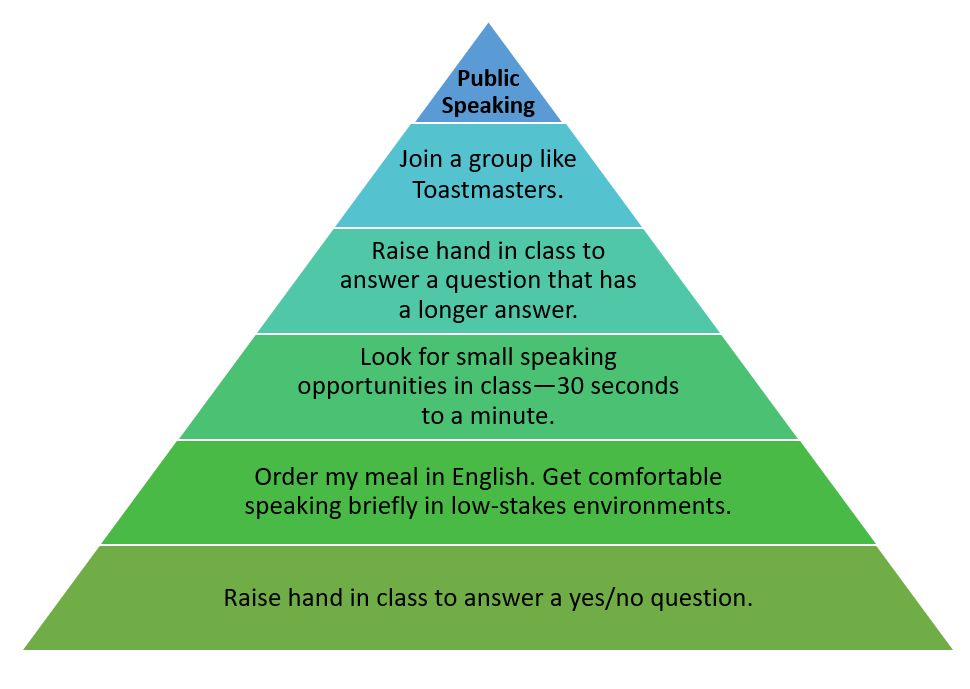

Technique 1. Gradual Exposure

Guiding Objective: The

purpose of gradual exposure is to incrementally become comfortable with

experiences that cause discomfort and resulting stress or anxiety.

Approach

-

Have students identify one task or aspect of the

course or class that would typically cause them direct or indirect stress or

anxiety.

-

Then, have students brainstorm as many achievable

microgoals as possible—microgoals that would support them with stronger

feelings of ease along with the stressful event. Map the microgoals in order

from least stressful to most stressful, with the final stressful event at the

top.

-

Teach students that the goal is to make progress,

and if they were only able to surpass their first microgoal, even that would be

progress.

-

Provide an example (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gradual exposure example.

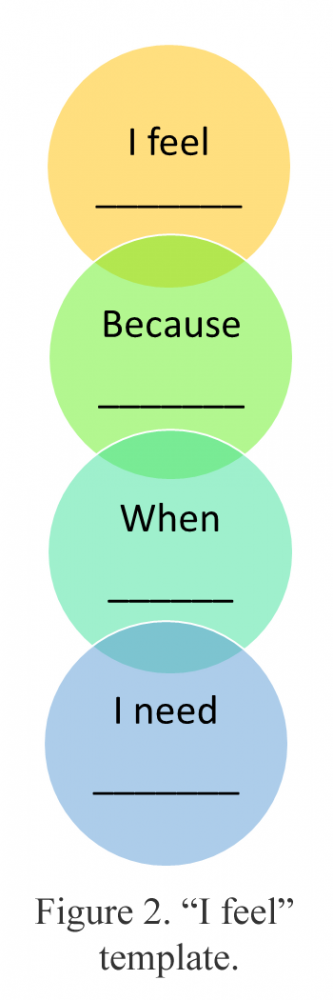

Technique 2. “I feel” Statements

Guiding Objectives: “I

feel” statements establish ownership of one’s feelings and consequently

initiate personal accountability. The goal is to normalize talking about how

students feel in relation to stress and/or anxiety, explore why they might feel

that way, and support an environment where they express what they need.

Approach

Approach

-

Establish a regular practice of “checking in”

with how students feel about a class-related task, happenstance, or event.

-

Consider having an “I feel” poster in your

classroom or a section in your course syllabus.

-

Teach how to effectively express “I feel”

statements using a template similar to the one shown in Figure 2.

-

Provide examples:

Example 1

-

I feel anxious because I don’t think my language ability is good

enough to deliver a presentation.

-

When I speak in

public at my level of ability, I stutter and even forget what I am supposed to

say.

-

I need more practice

and to feel comfortable making mistakes as I grow.

Example 2

-

I feel frustrated because I studied very hard for my reading

comprehension/oral communication exam, and I earned a grade lower than I

expected.

-

When I see my grade

lower than where I think my progress is, I feel like giving up.

-

I need to practice

having a growth mindset, to understand that progress is not linear, and to

believe that I am going to eventually achieve my goals.

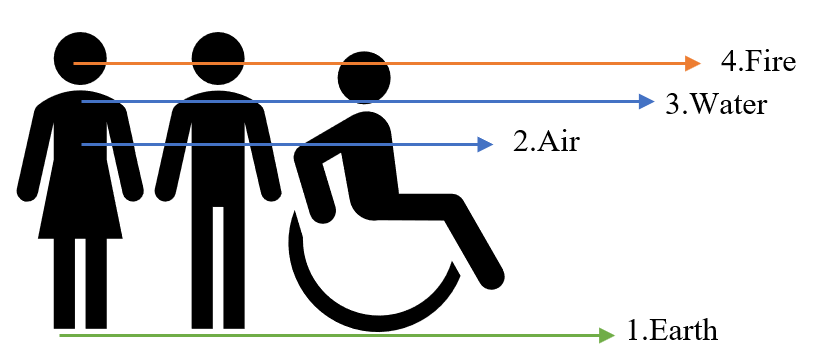

Technique 3. Four Elements of Stress Reduction (Shapiro,

2012)

Guiding Objectives: Shapiro’s (2012) four elements of stress reduction—earth, air,

water, and fire—promotes the practice of keeping your stress levels within a

window of tolerance by implementing four grounding exercises that redirect

attention outward and inward. The intention is to, in each part of your body

(see Figure 3), work through moments where you feel flooded by feelings of

stress tied to a class-related event through acknowledgement, acceptance, and

release.

Approach

Figure 3. Anatomical view of Shapiro’s (2012) four

elements of stress reduction.

-

In the early weeks of an academic session,

introduce students to the concept of self-regulation and emphasize the

importance of checking in with oneself.

-

Underscore the principle that self-checks are a

form of self-respect and self-care—both being characteristics of resilient and

motivated lifelong learners.

-

Teach students how to do Shapiro’s four elements

using an example like the following:

Example

Teacher: Acknowledge stressful

feelings and self-regulate by doing as many of the four steps as you

can:

1. Earth: Get grounded

by connecting with the earth. This could be taking your shoes off and taking a

barefoot walk, even if it is brief. Or, getting grounded could be tapping your

feet to a rhythm that is comforting. Even bolder, ground yourself by putting on

your favorite song and dancing. The idea is to move.

2. Air: Breathe by

putting your left hand on your heart and your right hand on your stomach and

inhaling for four counts and exhaling for seven counts. The idea is to slow

down your nerves, and connecting with your breath is most effective.

3. Water: Taste

something that will liven up or refresh you. This could look like drinking a

cup of comforting tea or sucking on a peppermint candy.

4. Fire: Imagine your

safe and happy place. As you pull up this image in your mind, place yourself in

it and think about how you feel when experiencing your comforting space. Allow

yourself to dwell on that thought for a minute before repositioning yourself in

your circumstance or environment.

Technique 4. Self-Scan, Awareness, and Containment

Guiding Objectives: Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk (2014) is known for saying “The

body keeps the score.” A body that keeps the score, a dysregulated body, is

often unmotivated to learn because it is under duress. By teaching students the

practice of drawing awareness to how one is feeling, they can then learn how to

direct feelings to an appropriate place in one’s experience—a form of

containment. Cultivating an atmosphere where acknowledging how students feel in

the classroom as a regular component of the day’s agenda brings balance to the

era of “leave your feelings at the door” in education and academia.

Approach

-

Be in tune with your class and make it a

conscientious point to take the social-emotional pulse of your students as they

enter. This might look like making eye-contact and addressing students by name

as you welcome them to class. Look for verbal and nonverbal cues to determine

whether this mindfulness technique is appropriate for the day.

-

Consider adopting a mindfulness warm-up practice

in the first 10 minutes of class where you walk students through a body scan.

Here is an example:

Example

Teacher: Good morning. Welcome

to class. I invite you to participate in a brief warm-up before we dive into

our lesson today. Participation is optional. If you choose not to participate

in our warm-up, take these next 5 minutes to center (focus) yourself ahead of

our time together.

Self-Scan and

Awareness

Are we ready?

-

Close your eyes in 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

-

Ease (become comfortable) into your seat and into

this classroom.

-

We’ll begin by becoming aware of our breath.

-

At your own pace, take three breaths. Inhale

(breathe in) and slowly exhale (breathe out). [Wait 5 breaths.]

-

Become aware of any tension or discomfort you

might feel. What is weighing you down today? What might be occupying your

thoughts?

Containment

-

As you become aware of how you are feeling,

acknowledge yourself and direct those feelings to where you want them to go.

This could be in a container on a shelf or even in box that you dump in an

ocean.

-

Remind yourself that you can always revisit what

is bothering you or occupying your thoughts at any time, but that you are

choosing to acknowledge and contain them for our class time together.

Closing

-

Once you have directed your feelings to where you

want them to go during our time together, take three breaths at your own pace.

[Wait 5 breaths]

-

Now, open your eyes in 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Technique 5. Reframing Automatic Negative Thoughts (ANTs)

Guiding Objectives: Conceptually designed from the work of Beck et al. (1979) and

later coined and further developed by psychiatrist Amen (2015), the term

“automatic negative thoughts” (ANTs) refers to the proliferation of one’s

long-held automatic negative beliefs. Students often curate narratives of what

they might have been told their strengths or weaknesses are in a subject or

academic history and use those frames for how they position themselves in class

and how they see themselves as independent language learners. Whether the

negative thought be categorized as catastrophizing, labeling, mind reading, or

blaming—just to name a few ANTs categories—the thought presents a cognitive

distortion that needs reframing so students can progress. The objective is

first to help train the mind to identify ANTs and afterwards, to reframe them.

Approach

-

Teach students the concept that our brains

believe what we tell them and, like anything else, the brain becomes what we

feed it. So, it is best to feed it a great diet.

-

Briefly walk students through a reframing ANTs

exercise like the following:

Teacher: We often have ANTs

that can influence how we view ourselves and even learn and grow. For me, your

professor, this is what my ANT sounded like: “I’m not good at math. I’ve never

been good at math. I’ll never be good at math. So, I’ll stick to what I’m good

at—reading and writing.” For someone learning a new language, an ANT might

sound like this: “Others laugh at my pronunciation, so it is better if I stay

quiet. If I don’t speak up, I will never be humiliated.” ANTs are like

jokes—they only have a little bit of truth to them. ANTs are not the whole picture we want to believe.

Practice

-

First, take 1–2 minutes and write down one or

more ANTs that often come up for you while in our class. You are the only

person who is going to see your ANTs.

-

Then once you have your ANTs down, answer these

questions about them:

-

My ANTs are 100% true all the time. ❏ Yes ❏

No

-

My ANTs define who I am. ❏ Yes ❏ No

-

My ANTs are the reality I want. ❏ Yes ❏

No

-

Chances are all your answers to the checklist

above are NO!

-

Finally, write down what I like to call “positive

encouraging thoughts” (PETs). PETs counter your ANTs. Your PETs are what you want to think about and believe. For me, my PET sounds

like this: “Math can often be difficult for many people. Some concepts are

easier than others for me to learn. Like other things that I learn, practice

and progress are what I choose to believe I am capable of.”

-

For you, a PET for pronunciation skills while

learning a new language might sound like this: “Learning and speaking an

additional language proves how capable I am. I have language abilities that

others may not have, and I am unique. My accent is part of who I am. Other

people’s ability to understand me is what is important, not having perfect pronunciation. What people think about

me is their problem—not mine.”

-

Repeat this process daily to avoid ANTs and keep

PETs!

Conclusion

Often, teachers and students alike enter the

classroom with conscious and unconscious assumptions of each other and the year

or semester ahead. We must remember that our language learners enter our

classrooms with an entire history of which we do not know, and stress and

anxiety may very well be exacerbated by classroom happenings. The task at hand

is clear—to provide multilingual learners of English with the knowledge and

tools necessary to achieve learning gains and, hopefully, establish an

environment in which they have ease and joy doing so.

References

Amen, D. G. (2015). Change your brain,

change your life: The breakthrough program for conquering anxiety, depression,

obsessiveness, lack of focus, anger, and memory problems. Harmony

Books.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B., & Emery,

G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford

Press.

Shapiro, E. (2012). 4 elements exercises

for stress reduction (earth -air -water -fire).https://emdrfoundation.org/toolkit/four-elements.pdf

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps

the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma.

Penguin Books.

Dr. Saghar Leslie Naghib, a second generation Persian American and Miami native, is a senior lecturer of English language with Duke Kunshan University’s Language and Culture Center and an advocate for normalizing the role of a positive mental health approach in education and academia.