Collaborative Reading in a Virtual World

by Lin Zhou and Natalya Watson

Reading is a vital skill in a university learning

environment. International students, however, frequently underestimate its

value based on the experience of preparing for standardized tests of English as

a foreign language. As Rosenwasser and Stephen (2015) remind us, to move beyond

reading for the gist and develop a deeper understanding of a text, readers

should become more actively engaged with the text materials by talking about

the reading conversationally with other people and being in “some kind of

dialogue with it, to see the questions the material asks, and to pose your own

questions about it” (p. 207).

Students engage in deconstructing a text by

identifying the structural elements and linguistic features that are valued in

a particular discipline (Cheng, 2018). They also exchange insights and negotiate

roles while working together to construct meaning. In some cases, students may

lead discussions among their peers by offering critical comments and asking

challenging questions to uncover implicit meanings. This collaboration helps

learners process a complex text by reducing the cognitive and emotional

demands, which, ultimately, leads them to the realization that reading is a

social activity (Su et al., 2018). Further, when a collaborative reading task

is supported by technology, students’ interest and motivation to contribute in

class activities increase.

In this article, we describe an activity called

Collaborative Reading in a Virtual World (VW), during which students use their

avatars in a virtual environment to discuss reading materials as a group. This

activity was created to encourage students to critically read with their peers

by discussing an assigned reading with one another in an environment where they

feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas. Benefits of collaborative reading

include

- peer support,

- clarification of understandings,

- attention to details in a reading, and

- generation of new ideas.

A VW is a more dynamic online environment than

other conferencing tools because teachers can design the world based on the

students’ emergent needs. For instance, a collaborative board can be built in

the VW when students feel they need to take notes while discussing a reading.

See Figure 1 for an example of a dynamic VW build around student needs and

interests.

Figure 1. Screenshot showcasing a corner of our

departmental VW in which instructors can host end-of-semester

parties.

To conduct the collaborative reading activity,

you’ll first need to create a VW and familiarize yourself with the world as you

create it. Then, you’ll allow students to explore (or assign small tasks) to

let them familiarize themselves with the VW before you assign the activity of

collaborative reading.

1. Create a Virtual World

There are many different types of VWs available

online; however, for the purpose of this activity, you’ll need a platform that

allows users to build their own artifacts in the VW (e.g., Second Life or the

Sims), because this affords various kinds of pedagogical activities.

In addition, these platforms give the designers ownership of their designed

worlds and can limit access to only eligible users.

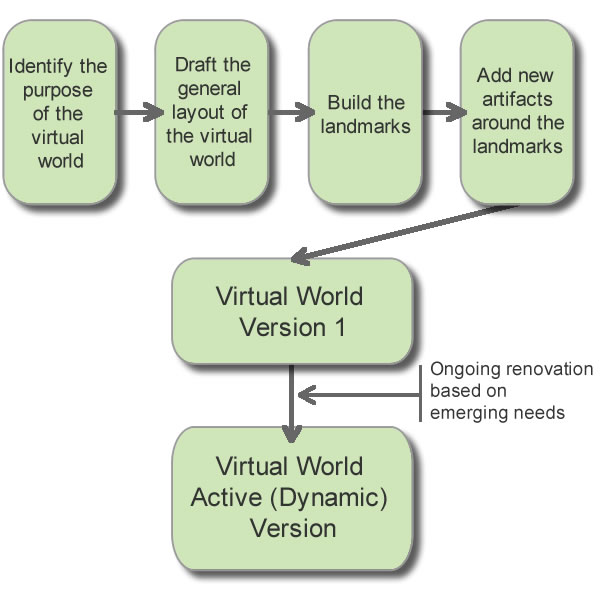

Figure 2 depicts the process of creating a

VW.

Figure 2. Steps to create a virtual

world.

To create a VW that can be used for multiple

classes, it is important to start with a clear objective. Once a theme is set,

you can build the landmarks first, and small artifacts can be built around the

landmarks based on the functions of the landmarks and the layout of the region.

An ideal VW is dynamic—it can be constantly updated

based on emerging needs. For example, if you plan to hold a virtual

presentation session, you can build conference rooms, interactive screens,

tables, and chairs in one or several of the buildings you’d already built in

the VW.

Although the creation of a VW might seem a daunting

task, language teachers have many options:

-

Create a simple VW with fewer artifacts for your

own classes.

-

Form a team with other teachers; work together to

create a comparatively complex VW and share the virtual space for different

purposes.

-

Involve students in cocreating a VW.

2. Let Students Explore

To maximize the benefit of collaborative reading in

a VW, students must be familiar with the relevant technologies and prepared to

meet with their peers in the world. Before beginning the activity, you can help

students become familiar with all the basic functions inside a VW, such

as

- talking using an avatar,

- moving around (walking, running, and flying),

- teleporting to different locations, and

- using embedded collaborative boards or other

tools.

Once students become adept at the VW technologies,

you can model how to read collaboratively in a VW.

3. Assign the Collaborative Reading Activity

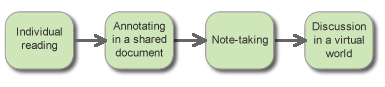

There are several key steps in this activity for

students to make meaningful contributions to the joint discussion.

Collaborative reading in a VW generates a learning process (see Figure 3) in

which students read individually first, annotate in a shared document, and then

take thoughtful notes that end with discussion in the VW.

Figure 3. Collaborative reading process.

Preread and

Annotate

It is essential for students to read individually

in advance so that they can formulate questions to discuss with their peers

when they meet in the VW. Divide students into groups of three to four and have

each group annotate a reading using different colors in a collaborative

document, such as in Google Docs. Annotations are key in this activity because

they prompt students to ask each other questions. When students meet in the VW

and look at the annotated reading, they can see how they annotated differently,

and these differences in annotation will lead to conversations about their

understanding of a reading.

Take on

Roles

Students may take on different roles in the joint

task; assigning these roles can ensure active participation from each person.

For example, one student can be a lead discussant while other students can be

assigned to summarize main points raised by their peers or become word masters

(defining unfamiliar terms). Another responsibility may be to provide an in-depth

commentary on a selected passage.

Discuss the

Reading

When students meet in the VW, they will teleport to

a location they have agreed upon before the meeting where they will be able to

see a collaborative board on which everyone can write while discussing. The

group member whose role is to lead the discussion can begin by listing the

questions each member had about the reading.

Figure 4 captures a group engaging in collaborative

reading in the VW; the group was discussing the concept of “deepfake” that came

up from the reading material. Record the collaborative reading sessions for

further reflections as a postreading activity.

Figure 4. Screenshot of a collaborative reading

session.

Other Uses for Virtual Worlds

A VW has many potential uses in language learning

classrooms. Once you’re comfortable as a VW designer and know what things your

students relate to, you can create meaningful spaces with different

function-carrying artifacts based on the needs of your students and your

classroom activities.

In addition to reading, you can also use VWs for

writing and public speaking. Some activities include

- designing a writing process in a group,

- group free writing,

- mock public speeches, and

- debates.

Conclusion

Based on student feedback, collaborative reading in

a VW has been shown to be effective in our reading classes. Students enjoy the

novelty of using their avatars to read with their peers. Instead of treating

reading as an individual activity, they embrace the opportunity to participate

in social regulation by providing input into one another’s annotations and

sharing what they found interesting, confusing, and even frustrating about a

reading. Because we asked students to record their virtual collaborative

reading sessions, they reported that they were motivated to read an assigned article

in depth to have a more robust discussion.

The process of discussing a text in a virtual space

allows students to dialogue with the reading materials in depth and have more

opportunities to think critically about the text, both in terms of ideas and

linguistic choices to express them.

References

Cheng, A. (2018). Genre and

graduate-level research writing. University of Michigan

Press.

Rosenwasser, D., & Stephen, J. (2015). Writing analytically. Cengage Learning.

Su, Y., Li, Y., Hu, H., & Rosé, C. P.

(2018). Exploring college English language learners’ self and social regulation

of learning during wiki-supported collaborative reading activities. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning, 13(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-018-9269-y

Lin Zhou is an assistant teaching professor in the NU Global program of Northeastern University. Specializing in pedagogical game design and innovative course design, Dr. Zhou promotes and practices teaching that revolves around experiential learning, project-based instruction, and game-supported pedagogies. A frequent speaker at international conferences, she has presented papers on topics including language learning with an augmented reality mobile game, translanguaging in pedagogical drama gaming, and an ecological approach to an online second language writing course.

Natalya Watson holds a master’s in TESOL from Northern Arizona University and a doctorate in education from the University of Colorado Denver. She teaches in the Global Pathways Program at Northeastern University of Boston. Her research interests include academic literacy of second language learners, genre analysis, and English for specific purposes. She frequently presents her work at TESOL and AAAL.