With the movements toward digitalization in workplaces and virtual classrooms, different skills are needed to get a job and do it well. The skills that undergird workplace literacy today range from understanding and responding to published materials to inputting and using digital information (Casner-Lotto & Barrington, 2006). Adult English as a second language (ESL) learners can no longer rely only on becoming orally proficient in English to obtain and keep a job; they need reading and writing skills to ensure their success in jobs and in higher education. To better reflect the skills that adult English learners need, adult education’s governing bodies in the United States have refined their accountability systems, adopting new English Language Proficiency Standards (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education, 2016) and changing the essay task on high school equivalency exams.

In this article, the third in our series on second language writing in adult education, I give a brief overview of high school equivalency exams and the skills learners need to pass them. I then describe, through an extended example, how standards-based lessons can help learners acquire these skills. (See Part 1 and Part 2 of the series.)

High School Equivalency Exam Writing Tasks

After exiting adult ESL programs, adult English learners can prepare to take one of the three high school equivalency exams:

- General Educational Development (GED)

- High School Equivalency Test (HiSET)

- Test Assessing Secondary Completion (TASC)

Each test contains a section for language arts, which includes a written essay. Originally, the writing sample in the GED, the oldest of the three tests, was a five-paragraph essay based on the learner’s experience. In 2014, when the GED was revised and the HiSET and TASC were developed, this task was altered; all three tests instead utilize read-to-write tasks. A read-to-write task is a task in which the student reads two or more source materials and then responds to a prompt by writing an essay that uses information from the source materials as support (Hirvela, 2016). The two source materials provided each show one side of an issue. These read-to-write tasks are thought to more closely mirror university writing assignments and thus be a more authentic measure of students’ academic writing ability (Carson, 2001).

This new approach to assessing students’ academic writing skills also tests their reading abilities. In 45 minutes, students need to be able to

- read the materials provided and understand them;

- read the writing prompt and determine what they are being asked to produce; and then

- use the materials provided to write an essay that conforms to the guidelines of the prompt and demonstrates their academic writing skills.

For example, a practice GED read-to-write task gives students two pieces of writing, one arguing that school lunches should be 100% vegetarian to improve students’ health and combat the obesity epidemic, and the other arguing that animal protein is necessary for great athletic performance and to sustain energy in children (GEDpracticetest.net, n.d.). Each piece has sources, or appeals to authorities, to support its main argument. Students need to weigh the evidence and decide which argument is stronger. Then, they write an essay arguing for that side and use source material from both sides. The HiSET and the TASC also ask students to write an essay arguing for one side using the material from two sources with opposing opinions on a topic; however, the students can choose either side—they do not need to argue for the side having the stronger evidence.

What are ways that we can prepare students to pass these exams? One accountability system gives a roadmap to help students acquire the skills they need to pass a high school equivalency exam: the English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education (ELP Standards).

English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education

Released in 2016, after extensive research and vetting, the ELP Standards reflect the 2013 College and Career Readiness Standards and guide teachers and program administrators in planning. They consist of 10 standards, each delineated at five English language proficiency levels. Standards 1–7 detail the English language skills learners need to do academic work in English across all disciplines. Standards 8–10 address specific linguistic skills, such as grammatical conventions and word meanings, needed to fulfill Standards 1–7. (For a fuller description of the ELP Standards and planning a standards-based lesson, see Rubio-Festa, 2019.)

In planning lessons so students can successfully write for a read-to-write task, it is helpful to use the ELP Standards. Standards 3, 4, and 6 specifically outline the skills learners need to acquire to successfully complete a read-to-write task:

-

Standard 3: An English language learner (ELL) can speak and write about level-appropriate complex literary and informational texts and topics.

-

Standard 4: An ELL can construct level-appropriate oral and written claims and support them with reasoning and evidence.

-

Standard 6: An ELL can analyze and critique the arguments of others orally and in writing.

Preparing students to be successful on a read-to-write task does not mean beginning to prepare them when they reach an advanced level of proficiency. This is a common misperception that we found in our research (Fernandez et al., 2017). Students at all levels of proficiency can develop the habits of mind needed for academic and professional reading and writing (Schaetzel, 2019).

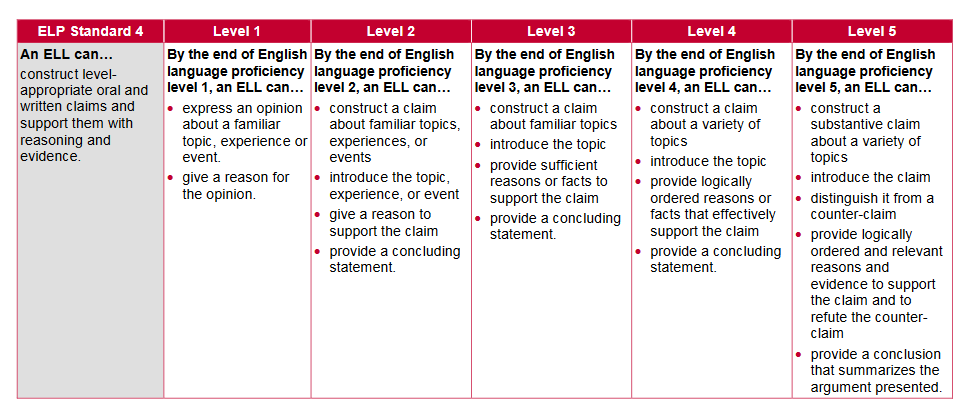

To plan class activities for all levels for any given standard, we would begin by examining the skill descriptors for each level. We’ll use Standard 4 as an example:

Figure 1. Adult English Language Proficiency

Standards for Adult Education, Writing Standard 4. Reproduced from the “Adult

English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education” by the U.S.

Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education, 2016,

p. 45. (Click here to enlarge)

Activities for each of these proficiency levels can incorporate reading, writing, listening, and speaking tasks that support the development of the ability to construct “level-appropriate oral and written claims and support them with reasoning and evidence.” The end goal of this work, if students need to take a high school equivalency exam, is that they will be able to adopt an opinion expressed in a piece of writing and use information from the two sources provided to support their opinion.

What tasks at each level can move students towards this goal? (Activities that use written text also meet the criteria for Standard 3.) Following, I provide examples of activities for each level of proficiency to help students master this skill.

Level 1: Students need to be able to express an opinion about a familiar topic, experience, or event, and give a reason for the opinion.

Classroom Activity

This activity is a version of “show and tell.” Ask students to bring a picture of something they like or want, or they can find pictures from magazines during class. First, have them state an opinion about why they like or want what is in the picture. Write their sentence on the board. Second, have students give one or two reasons for their opinion. Write these sentences on the board and have the students copy what you wrote. For example, “I like pink nail polish” expresses their opinion. Reasons, such as “It is a happy color” and “It matches a lot of my clothes,” then follow. (This can also be done with fill-in-the-blank sentences, and you can circulate, helping students fill in the blanks.)

Level 2: Students need to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, give a reason to support the claim, and provide a concluding statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity uses a passage from the students’ textbook or other written source about a familiar topic, experience, or event. The students read the passage and answer a question about it—the answer to the question should be framed as a claim. For example, if the passage is about couples changing their last names after they marry, questions can include: “Do you agree that couples should change their names after marriage?” or “Why should/shouldn’t married people change their names after they marry?” Students answer the question, which is their “claim.” They then list one or more reasons why they have this opinion. Finally, they write a concluding statement, restating their claim. You can scaffold this activity the first time students engage in it by providing fill-in-the-blank sentences or having students work in pairs and orally state their claim and reason(s) before writing them.

Level 3: Students need to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, provide sufficient reasons or facts to support the claim, and provide a concluding statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity guides students in using facts and reasons to support an opinion. First, they read a passage that presents one side of a controversial issue (e.g., whether banks should charge fees for account services, or whether it is better to wash your car by hand or use a car wash). Then, they fill out a graphic organizer to identify the main claim and list the support for the claim that the reading presents. Then, in another, similar graphic organizer, they list the opposite claim and think of reasons and facts to support the other side of the issue. (If possible, they may research and find information in sources.) Students then write a passage arguing for the claim that their original article presented and give reasons and facts to support this side. (See Part 2 of this series for tips on using graphic organizers.)

Level 4: Students need to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, provide logically ordered reasons or facts that effectively support the claim, and provide a concluding statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity introduces students to two written pieces that state different opinions about a topic. For example, they can read two texts about whether video games are good for children. Working in pairs, they fill out a graphic organizer that lists the reasons video games are good and recommended, and the reasons that video games may be harmful. They can also add their own opinions below the graphic organizer.

After learning how to introduce source material in writing, students can work individually or in pairs to write in support of one opinion about video games, using material from both texts to support their point of view (agreeing with one text and disagreeing with the other). If scaffolding is needed, you can provide a frame for the topic sentence and the markers “first, second, third,” and so on to enumerate support. (Students in pairs can also each write differing sides of this argument and then compare their pieces. Oral argumentation can also be used to scaffold before writing or to have a class debate after writing.)

Level 5: Students need to be able to construct a claim, introduce the claim, distinguish it from a counter-claim, provide logically ordered and relevant reasons to support the claim and to refute the counter-claim, and provide a conclusion that summarizes the argument.

Classroom Activity

This activity asks students to identify a claim and a counter-claim using two articles that have opposing points of view. For example, one article might show the value of recycling, and the other might state that recycling is not important, or one article might say the government should continue to provide free public libraries/public schools, and another might show that free public libraries/public schools are too expensive for the government.

Students can use graphic organizers to delineate support for each side and determine strong and weak arguments. One common, easy method for deciphering strong and weak arguments is called STAR: Is the evidence Specific, Typical, Accurate, and Relevant? (Ramage et al., 2011). Students can then write an essay in a pair or individually stating the side they agree with (or, if studying for the GED, the side that has the strongest arguments) and then use information from both sources to establish their arguments.

For All Levels: An activity that can be used in some form at any of these levels involves using Elbow’s (1986) “the believing game” and “the doubting game.”

Classroom Activity

Through different ways of reading, students can begin to figure out which arguments are strong and which are weak. Have students read a passage and play “the believing game” by believing and accepting everything the author says. Then, have the student reread the same passage while playing “the doubting game,” in which they doubt and question everything the author says. This game makes an excellent oral scaffold before students write. It can also be played in a pair where one student believes and the other student doubts.

Conclusion

After examining the types of read-to-write tasks embodied in high school equivalency exams, the ELP Standards provide clear, concise guidance to help you fashion lessons that will enable learners to succeed on these exams. The ELP Standards and the read-to-write tasks mirror reading and writing tasks that learners will encounter in higher education and professional settings. Introducing students to these tasks and the skills they develop will build their confidence and, in turn, empower them to achieve their goals.

We hope that our series on second language writing has presented some interesting and innovative ways to vary lessons and bring different ways of learning into classes. In our first piece, Rebeca Fernandez delineates writing-enhanced content-based instruction; in our second piece, Joy Peyton reviews and introduces new instructional approaches and scaffolds. In this final piece, Kirsten Schaetzel demonstrates ways of using standards-aligned instruction to help learners succeed on high school equivalency exams.

References

Carson, J. (2001). A task analysis of reading and writing in academic contexts. In D. Belcher & A. Hirvela (Eds.), Linking literacies: Perspectives on L2 reading-writing connections (pp. 246–270). University of Michigan Press.

Casner-Lotto, J., & Barrington, I. (2006). Are they really ready to work? Employers’ perspectives on the basic knowledge and applied skills of new entrants to the 21st century U.S. workforce. The Conference Board. http://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=796672

Elbow, P. (1986). Embracing contraries: Explorations in learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Fernandez, R., Peyton, J. K., & Schaetzel, K. (2017, Summer). A survey of writing instruction in adult ESL programs: Are teaching practices meeting adult learner needs? Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education, 6(2), 5–20.

GEDpracticetest.net. (n.d.). GED essay writing guide. https://gedpracticetest.net/ged-essay-guide/

Hirvela, A. (2016). Connecting reading & writing in second language writing instruction (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

Ramage, J. D., Bean, J. C., & Johnson, J. (2011). Writing arguments: A rhetoric with readings. Pearson Education.

Rubio-Festa, G. (2019). Teaching writing in an age of standards. In K. Schaetzel, J. Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult learners to write for college and the workplace (pp. 234-253). The University of Michigan Press.

Schaetzel, K. (2019). Using test prompts to develop academic writing. In K. Schaetzel, J. Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult learners to write for college and the workplace (pp. 211-233). The University of Michigan Press.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education. (2016). English language proficiency standards for adult education. American Institutes for Research. https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/elp-standards-adult-ed.pdf

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Kirsten Schaetzel is the English language specialist at Emory University School of Law. She works with students on English skills, especially academic reading and writing. She has taught in university and adult education programs in the United States, Singapore, Macau, and Bangladesh.

| Next Article |