Adult Learners in SLW (Part 3): Standards-Aligned Instruction

by Kirsten Schaetzel

With the movements toward digitalization in workplaces and

virtual classrooms, different skills are needed to get a job and do it well. The

skills that undergird workplace literacy today range from understanding and

responding to published materials to inputting and using digital information

(Casner-Lotto & Barrington, 2006). Adult English as a second language

(ESL) learners can no longer rely only on becoming orally proficient in English

to obtain and keep a job; they need reading and writing skills to ensure their

success in jobs and in higher education. To better reflect the skills that

adult English learners need, adult education’s governing bodies in the United

States have refined their accountability systems, adopting new English Language

Proficiency Standards (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career,

Technical and Adult Education, 2016) and changing the essay task on high school

equivalency exams.

In this article, the third in our series on second

language writing in adult education, I give a brief overview of high school

equivalency exams and the skills learners need to pass them. I then describe,

through an extended example, how standards-based lessons can help learners

acquire these skills. (See Part

1 and Part

2 of the series.)

High School Equivalency Exam Writing

Tasks

After exiting adult ESL programs, adult English

learners can prepare to take one of the three high school equivalency exams:

- General Educational Development (GED)

- High School Equivalency Test (HiSET)

- Test Assessing Secondary Completion

(TASC)

Each test contains a section for language arts,

which includes a written essay. Originally, the writing sample in the GED, the

oldest of the three tests, was a five-paragraph essay based on the learner’s

experience. In 2014, when the GED was revised and the HiSET and TASC were

developed, this task was altered; all three tests instead utilize read-to-write

tasks. A read-to-write task is a task in which the student reads two or more

source materials and then responds to a prompt by writing an essay that uses

information from the source materials as support (Hirvela, 2016). The two

source materials provided each show one side of an issue. These read-to-write

tasks are thought to more closely mirror university writing assignments and

thus be a more authentic measure of students’ academic writing ability (Carson,

2001).

This new approach to assessing students’ academic

writing skills also tests their reading abilities. In 45 minutes, students need

to be able to

- read the materials provided and understand them;

- read the writing prompt and determine what they

are being asked to produce; and then

- use the materials provided to write an essay that

conforms to the guidelines of the prompt and demonstrates their academic

writing skills.

For example, a practice GED

read-to-write task gives students two pieces of writing, one arguing

that school lunches should be 100% vegetarian to improve students’ health and

combat the obesity epidemic, and the other arguing that animal protein is

necessary for great athletic performance and to sustain energy in children

(GEDpracticetest.net, n.d.). Each piece has sources, or appeals to authorities,

to support its main argument. Students need to weigh the evidence and decide

which argument is stronger. Then, they write an essay arguing for that side and

use source material from both sides. The HiSET and the TASC also ask students

to write an essay arguing for one side using the material from two sources with

opposing opinions on a topic; however, the students can choose either side—they

do not need to argue for the side having the stronger evidence.

What are ways that we can prepare students to pass

these exams? One accountability system gives a roadmap to help students acquire

the skills they need to pass a high school equivalency exam: the English

Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education (ELP Standards).

What are ways that we can prepare students to pass

these exams? One accountability system gives a roadmap to help students acquire

the skills they need to pass a high school equivalency exam: the English

Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education (ELP Standards).

English Language Proficiency

Standards for Adult Education

Released in 2016, after extensive research and

vetting, the ELP Standards reflect the 2013

College and Career Readiness Standards and guide teachers and program

administrators in planning. They consist of 10 standards, each delineated at

five English language proficiency levels. Standards 1–7 detail the English

language skills learners need to do academic work in English across all

disciplines. Standards 8–10 address specific linguistic skills, such as

grammatical conventions and word meanings, needed to fulfill Standards 1–7.

(For a fuller description of the ELP Standards and planning a standards-based

lesson, see Rubio-Festa, 2019.)

In planning lessons so students can successfully write

for a read-to-write task, it is helpful to use the ELP Standards. Standards 3,

4, and 6 specifically outline the skills learners need to acquire to

successfully complete a read-to-write task:

-

Standard 3: An

English language learner (ELL) can speak and write about level-appropriate

complex literary and informational texts and topics.

-

Standard 4: An ELL

can construct level-appropriate oral and written claims and support them with

reasoning and evidence.

-

Standard 6: An ELL

can analyze and critique the arguments of others orally and in

writing.

Preparing students to be successful on a

read-to-write task does not mean beginning to prepare them when they reach an

advanced level of proficiency. This is a common misperception that we found in

our research (Fernandez et al., 2017). Students at all levels of proficiency

can develop the habits of mind needed for academic and professional reading and

writing (Schaetzel, 2019).

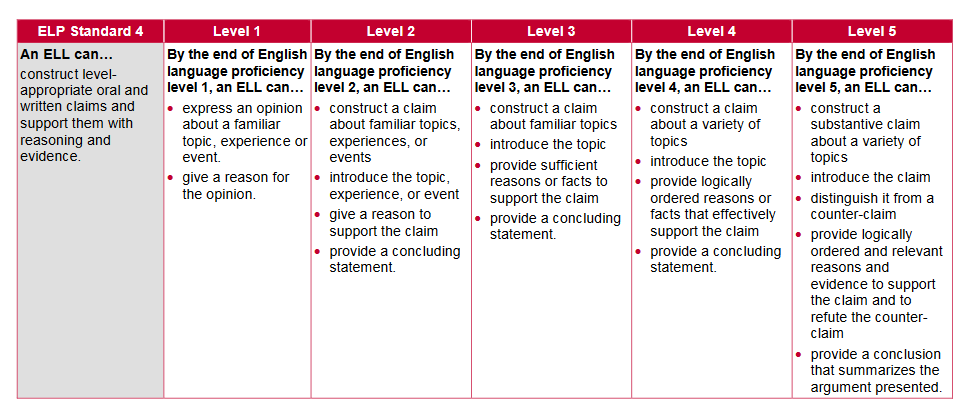

To plan class activities for all levels for any

given standard, we would begin by examining the skill descriptors for each

level. We’ll use Standard 4 as an example:

Figure 1. Adult English Language Proficiency

Standards for Adult Education, Writing Standard 4. Reproduced from the “Adult

English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education” by the U.S.

Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education, 2016,

p. 45. (Click here to enlarge)

Activities for each of these proficiency levels can

incorporate reading, writing, listening, and speaking tasks that support the

development of the ability to construct “level-appropriate oral and written

claims and support them with reasoning and evidence.” The end goal of this

work, if students need to take a high school equivalency exam, is that they

will be able to adopt an opinion expressed in a piece of writing and use

information from the two sources provided to support their opinion.

What tasks at each level can move students towards

this goal? (Activities that use written text also meet the criteria for

Standard 3.) Following, I provide examples of activities for each level of

proficiency to help students master this skill.

Level 1: Students need

to be able to express an opinion about a familiar topic, experience, or event,

and give a reason for the opinion.

Classroom Activity

This activity is a version of “show and tell.” Ask

students to bring a picture of something they like or want, or they can find

pictures from magazines during class. First, have them state an opinion about

why they like or want what is in the picture. Write their sentence on the

board. Second, have students give one or two reasons for their opinion. Write

these sentences on the board and have the students copy what you wrote. For

example, “I like pink nail polish” expresses their opinion. Reasons, such as

“It is a happy color” and “It matches a lot of my clothes,” then follow. (This

can also be done with fill-in-the-blank sentences, and you can circulate,

helping students fill in the blanks.)

Level 2: Students need

to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, give a reason to support

the claim, and provide a concluding statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity uses a passage from the students’

textbook or other written source about a familiar topic, experience, or event.

The students read the passage and answer a question about it—the answer to the

question should be framed as a claim. For example, if the passage is about

couples changing their last names after they marry, questions can include: “Do

you agree that couples should change their names after marriage?” or “Why

should/shouldn’t married people change their names after they marry?” Students

answer the question, which is their “claim.” They then list one or more reasons

why they have this opinion. Finally, they write a concluding statement,

restating their claim. You can scaffold this activity the first time students

engage in it by providing fill-in-the-blank sentences or having students work

in pairs and orally state their claim and reason(s) before writing them.

Level 3: Students need

to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, provide sufficient

reasons or facts to support the claim, and provide a concluding

statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity guides students in using facts and

reasons to support an opinion. First, they read a passage that presents one

side of a controversial issue (e.g., whether banks should charge fees for

account services, or whether it is better to wash your car by hand or use a car

wash). Then, they fill out a graphic organizer to identify the main claim and

list the support for the claim that the reading presents. Then, in another,

similar graphic organizer, they list the opposite claim and think of reasons

and facts to support the other side of the issue. (If possible, they may

research and find information in sources.) Students then write a passage

arguing for the claim that their original article presented and give reasons

and facts to support this side. (See Part

2 of this series for tips on using graphic organizers.)

Level 4: Students need

to be able to construct a claim, introduce the topic, provide logically ordered

reasons or facts that effectively support the claim, and provide a concluding

statement.

Classroom Activity

This activity introduces students to two written

pieces that state different opinions about a topic. For example, they can read

two texts about whether video games are good for children. Working in pairs,

they fill out a graphic organizer that lists the reasons video games are good

and recommended, and the reasons that video games may be harmful. They can also

add their own opinions below the graphic organizer.

After learning how to introduce source material in

writing, students can work individually or in pairs to write in support of one

opinion about video games, using material from both texts to support their

point of view (agreeing with one text and disagreeing with the other). If

scaffolding is needed, you can provide a frame for the topic sentence and the

markers “first, second, third,” and so on to enumerate support. (Students in

pairs can also each write differing sides of this argument and then compare

their pieces. Oral argumentation can also be used to scaffold before writing or

to have a class debate after writing.)

Level 5: Students need

to be able to construct a claim, introduce the claim, distinguish it from a

counter-claim, provide logically ordered and relevant reasons to support the

claim and to refute the counter-claim, and provide a conclusion that summarizes

the argument.

Classroom Activity

This activity asks students to identify a claim and

a counter-claim using two articles that have opposing points of view. For

example, one article might show the value of recycling, and the other might

state that recycling is not important, or one article might say the government

should continue to provide free public libraries/public schools, and another

might show that free public libraries/public schools are too expensive for the

government.

Students can use graphic organizers to delineate support

for each side and determine strong and weak arguments. One common, easy method

for deciphering strong and weak arguments is called STAR: Is the evidence Specific, Typical, Accurate, and Relevant?

(Ramage et al., 2011). Students can then write an essay in a pair or

individually stating the side they agree with (or, if studying for the GED, the

side that has the strongest arguments) and then use information from both

sources to establish their arguments.

For All Levels: An

activity that can be used in some form at any of these levels involves using

Elbow’s (1986) “the believing game” and “the doubting game.”

Classroom Activity

Through different ways of reading, students can

begin to figure out which arguments are strong and which are weak. Have

students read a passage and play “the believing game” by believing and

accepting everything the author says. Then, have the student reread the same

passage while playing “the doubting game,” in which they doubt and question

everything the author says. This game makes an excellent oral scaffold before

students write. It can also be played in a pair where one student believes and

the other student doubts.

Conclusion

After examining the types of read-to-write tasks

embodied in high school equivalency exams, the ELP Standards provide clear,

concise guidance to help you fashion lessons that will enable learners to

succeed on these exams. The ELP Standards and the read-to-write tasks mirror

reading and writing tasks that learners will encounter in higher education and

professional settings. Introducing students to these tasks and the skills they

develop will build their confidence and, in turn, empower them to achieve their

goals.

We hope that our series on second language writing

has presented some interesting and innovative ways to vary lessons and bring

different ways of learning into classes. In our first

piece, Rebeca Fernandez delineates writing-enhanced content-based

instruction; in our second

piece, Joy Peyton reviews and introduces new instructional approaches

and scaffolds. In this final piece, Kirsten Schaetzel demonstrates ways of

using standards-aligned instruction to help learners succeed on high school

equivalency exams.

References

Carson, J. (2001). A task analysis of reading and

writing in academic contexts. In D. Belcher & A. Hirvela (Eds.), Linking literacies: Perspectives on L2 reading-writing connections (pp. 246–270). University of Michigan Press.

Casner-Lotto, J., & Barrington, I. (2006). Are they really ready to work? Employers’ perspectives on the basic

knowledge and applied skills of new entrants to the 21st century U.S.

workforce. The Conference Board. http://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=796672

Elbow, P. (1986). Embracing contraries:

Explorations in learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Fernandez, R., Peyton, J. K., & Schaetzel,

K. (2017, Summer). A survey of writing instruction in adult ESL programs: Are

teaching practices meeting adult learner needs? Journal of Research

and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education,

6(2), 5–20.

GEDpracticetest.net. (n.d.). GED essay

writing guide. https://gedpracticetest.net/ged-essay-guide/

Hirvela, A. (2016). Connecting reading

& writing in second language writing instruction (2nd ed.).

University of Michigan Press.

Ramage, J. D., Bean, J. C., & Johnson, J.

(2011). Writing arguments: A rhetoric with readings. Pearson Education.

Rubio-Festa, G. (2019). Teaching writing in an age

of standards. In K. Schaetzel, J. Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult learners to write for college and the

workplace (pp. 234-253). The University of Michigan Press.

Schaetzel, K. (2019). Using test prompts to develop

academic writing. In K. Schaetzel, J.

Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult learners to

write for college and the workplace (pp. 211-233). The University of

Michigan Press.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career,

Technical and Adult Education. (2016). English language proficiency

standards for adult education. American Institutes for Research. https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/elp-standards-adult-ed.pdf

Kirsten Schaetzel is the English language specialist at Emory University School of Law. She works with students on English skills, especially academic reading and writing. She has taught in university and adult education programs in the United States, Singapore, Macau, and Bangladesh.